Sir Isaac Newton is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of all time, having made significant contributions to the fields of mathematics, physics, and astronomy. He is perhaps best known for his laws of motion and universal gravitation, which form the basis of classical mechanics. His work in these fields helped to lay the foundation for the scientific revolution, and his legacy continues to inspire new generations of scientists and mathematicians to this day.

Figure 1: Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton by Godfrey Kneller, 1689

Despite his many accomplishments in science, Newton was also a man of many interests, including economics and finance. He was a contemporary of the South Sea Company, one of the most infamous investment schemes of his time, and he was deeply involved in the company’s rise and fall.

Newton was recognized as a member of the British elite and lived well, with a horse-drawn coach and a retinue of servants. His total annual income of more than £3000 put him in the top 1% of the population, and not far from the top 0.1%. He did not overspend, was charitable, and saved a substantial fraction of his earnings. Land ownership was the traditional marker of British wealth and social status. Newton, however, never acquired any significant real estate. He was among the first to put his money mainly into financial instruments, a relatively new possibility at the time.

Sir Isaac Newtons investments were usually prudent and profitable. But then, late in life, he placed nearly all of his wealth into the stock of one company. It was the South Sea Company. Sir Isaac Newton was one of the many people who were lured by the prospect of making a fortune from the South Sea Company. He invested heavily in the company, buying shares at their peak.

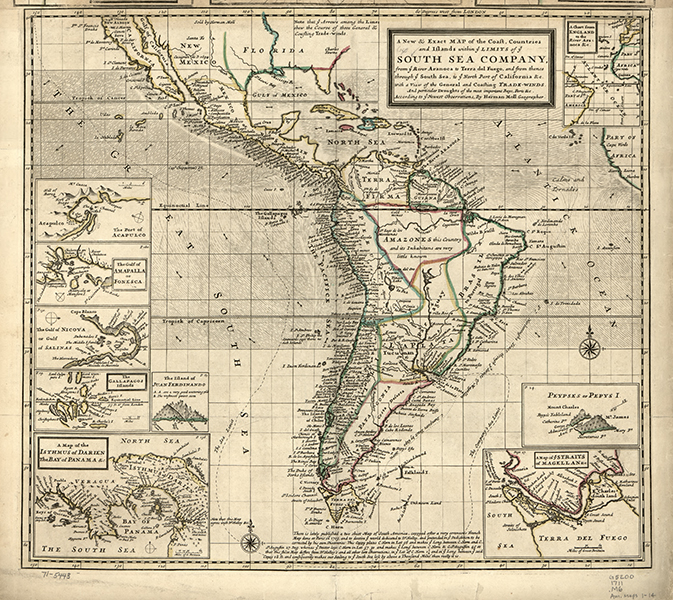

The South Sea Company

The South Sea Company was established in 1711 to deal with a pressing financial problem. The British government had a large backlog of unpaid bills, largely from contractors supplying the British military during the War of the Spanish Succession. The government offered its creditors South Sea stock, a product similar to shares in a modern corporation. The stock did not promise full repayment of the money creditors were owed, but it did promise them regular payment of interest.

Figure 2: South Sea Headquarters Bishop Gate, 1754.

The South Sea Company’s purpose was conducting trade with the Spanish South American colonies. It was granted a monopoly on trade in the South Seas, which led many investors to believe that the company was on the verge of great wealth and prosperity. The company’s shares were highly sought after, and as a result, the price of its shares rose rapidly.

During Newton’s period of accumulation, the war between Spain and England ebbed and flowed, curtailing South Sea Co.’s trading opportunities to the point where it remained unprofitable. Still, its shares enjoyed a gentle appreciation because of the prevailing notion that the trade monopoly would be fully implemented once a lasting peace was won. Scholars don’t have solid information about the profitability of the company’s trading activites; the evidence strongly suggests the company’s commercial operations lost money in those early years. However, the trade monopoly helped inspire dreams of future riches among the public.

Figure 3: Map of South Sea company’s monopoly area

What helped spread this belief was a new, burgeoning medium: the newspaper. The number of dailies in London, for example, went from one to 18 during the seven years to 1709. Glowing articles appeared, written in some cases by famous authors such as Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe. April 1720 also saw the publication of an unusually large number of pamphlets and newspaper articles about the economic fundamentals of the South Sea project, some of which Newton surely would have seen or discussed with contemporaries. On 14 April, a week after the passing of the South Sea Act, the South Sea Company offered some of its new shares to the public in the first of four sales. To stir up enthusiasm for the first sale, the company’s managers apparently arranged for the publication of an anonymous article in the newspaper Flying-Post on 9 April. The piece presented a vision for nearly infinite investor returns: the higher the price the South Sea Company could obtain for its new shares, the better its investors would fare.

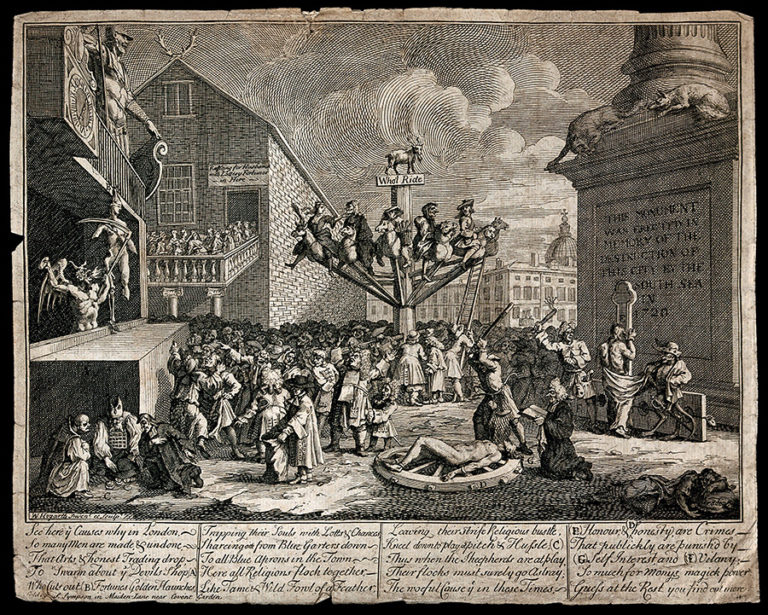

Its success caused a country-wide frenzy as all types of people, from peasants to lords, developed a feverish interest in investing: in South Seas primarily, but in stocks generally. One famous apocryphal story is of a company that went public in 1720 as “a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is”.

The Bubble

The South Sea Bubble was caused by a combination of factors, including overinflated stock prices, poor management, and widespread corruption. When the bubble bursted it lead to a financial crisis that had far-reaching effects across the entire country.

Sir Isaac Newton was one of the many investors who were left counting their losses, as the value of the company’s shares plummeted. Newton decided in the early stages of the mania that it was going to end badly and liquidated his stake at a large profit. Newton dumped his South Sea shares and gained a profit of £7,000. But the bubble kept inflating, and Newton jumped back in almost at the peak and lost £20,000 (or more than $3 million in today’s money). He continued to pour money into the South Sea stock even as its price was beginning to slide, before the precipitous collapse in September 1720. By that time, essentially his entire fortune was invested in South Sea. For the rest of his life, he forbade anyone to speak the words “South Sea” in his presence.

Figure 4: South Sea Stock price 1718-1721 made by Marc Faber sited in Business Insider

The story of Newton’s losses in the South Sea Bubble has become one of the most famous in popular finance literature; surveying his losses, Newton allegedly said that he could “calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

Newton himself was part of an immense crowd—an estimated 80–90% of all British investors—who were drawn into that economic spasm. Unlike astronomy, mathematics, and physics, finance was not an area where Newton towered over his contemporaries.

What you can learn from the cautionary story

Newtons tale shows that it is not the people with the highest IQ or with the best Academic record that do best in the stock market. In short, if you’ve failed at investing so far, it’s not because you’re stupid. It’s because, like Sir Isaac Newton, you haven’t developed the emotional discipline that successful investing requires.

Sir Isaac Newton was undoubtely one of the most intelligent people who ever lived, as most of us would define intelligence. But, Newton was far from being a great investor. By letting the roar of the crowd override his own judgment, the world’s greatest scientist acted like a fool. His experience provides an instructive example of how even brilliant thinkers can go astray in an environment that lends itself to collective delusions as a result of the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation

Figure 5:William Hogarth, Emblematical Print on The South Sea Scheme (1721) showing the foolishness of the crowd buying South Sea stocks.

IThe tale of Sir Isaac Newton shows that you should trust your own judgment and analysis and not be caught by the hype of the market or by herd behaviour.

In conclusion, Sir Isaac Newton’s investment in the South Sea Company is a cautionary tale about the dangers of investing in financial bubbles. It serves as a reminder that even the smartest and most successful people can be caught up in the hype of a speculative market and suffer significant losses as a result. Despite his vast knowledge and expertise, he was not immune to the irrationality of speculative bubbles, and suffered significant financial losses as a result of his investment in the South Sea Company. There is little sign that has changed over the ages as bubbles such as the dot-com bubble or the 2008 financial crisis shows that a investor should always be on watch. Therefore, the South Sea Company scandal should serve as a reminder to everyone of the dangers of speculative investing, and highlights the importance of caution and skepticism in the face of irrational exuberance and hype.