A bond is a fixed income instrument that represent a loan made by an investor to a borrower (typically corporate or government). Bonds are used by companies, municipalities, states, and sovereign governments to finance projects and operations. Owners of bonds are debtholders, or creditors, of the issuer. A bond is referred to as a fixed income instrument since bonds traditionally paid a fixed interest rate (coupon) to debtholders. Variable or floating interest rates are also now quite common. Bond prices are inversely correlated with interest rates: when rates go up, bond prices fall and vice-versa. Bonds have maturity dates at which point the principal amount must be paid back in full or risk default.

Governments and corporations commonly use bonds in order to borrow money. Governments need to fund roads, schools, dams or other infrastructure. The sudden expense of war may also demand the need to raise funds. Similarly, corporations will often borrow to grow their business, to buy property and equipment, to undertake profitable projects, for research and development or to hire employees. Large organizations often need more money than the average bank can provide, and bonds can be the solution by allowing many individual investors to assume the role of the lender. Moreover, markets allow lenders to sell their bonds to other investors or to buy bonds from other individuals—long after the original issuing organization raised capital.

Illustration 1: An original Bond Issue

The borrower (issuer) issues a bond that includes the terms of the loan, interest payments that will be made, and the time at which the loaned funds (bond principal) must be paid back (maturity date). The interest payment (the coupon) is part of the return that bondholders earn for loaning their funds to the issuer. The interest rate that determines the payment is called the coupon rate.

The initial price of most bonds is typically set at par, usually $100 or $1,000 face value per individual bond. The actual market price of a bond depends on a number of factors: the credit quality of the issuer, the length of time until expiration, and the coupon rate compared to the general interest rate environment at the time. The face value of the bond is what will be paid back to the borrower once the bond matures.

Most bonds can be sold by the initial bondholder to other investors after they have been issued. It is also common for bonds to be repurchased by the borrower if interest rates decline, or if the borrower’s credit has improved, and it can reissue new bonds at a lower cost.

Characteristics of Bonds

- Face value is the money amount the bond will be worth at maturity; it is also the reference amount the bond issuer uses when calculating interest payments. For example, say an investor purchases a bond at a premium $1,090 and another investor buys the same bond later when it is trading at a discount for $980. When the bond matures, both investors will receive the $1,000 face value of the bond.

- The coupon rate is the rate of interest the bond issuer will pay on the face value of the bond, expressed as a percentage. For example, a 5% coupon rate means that bondholders will receive 5% x $1000 face value = $50 every year. Two features of a bond—credit quality and time to maturity—are the principal determinants of a bond’s coupon rate. If the issuer has a poor credit rating, the risk of default is greater, and these bonds pay more interest. Bonds that have a very long maturity date also usually pay a higher interest rate. This higher compensation is because the bondholder is more exposed to interest rate and inflation risks for an extended period. Credit ratings for a company and its bonds are generated by credit rating agencies like Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch ratings.. The very highest quality bonds are called ‘investment grade’ and include debt issued by the U.S. government and very stable companies, like many utilities. Bonds that are not considered investment grade, but are not in default, are called ‘high yield” or “junk” bonds. These bonds have a higher risk of default in the future and investors demand a higher coupon payment to compensate them for that risk.

- Coupon dates are the dates on which the bond issuer will make interest payments. Payments can be made in any interval, but the standard is semiannual payments.

- The maturity date is the date on which the bond will mature and the bond issuer will pay the bondholder the face value of the bond.

- The issue price is the price at which the bond issuer originally sells the bonds.

Bonds and bond portfolios will rise or fall in value as interest rates change. The sensitivity to changes in the interest rate environment is called “duration”. The use of the term duration in this context can be confusing to new bond investors because it does not refer to the length of time the bond has before maturity. Instead, duration describes how much a bond’s price will rise or fall with a change in interest rates.

Categories of Bonds:

Corporate bonds are issued by companies. Companies issue bonds rather than seek bank loans for debt financing in many cases because bond markets offer more favorable terms and lower interest rates.

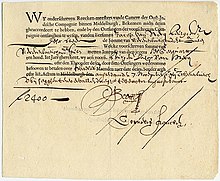

Illustration 2: Bond issued by the Dutch East India Company in 1623

Municipal bonds are issued by states and municipalities. Some municipal bonds offer tax-free coupon income for investors.

Government bonds such as those issued by the U.S. Treasury. Bonds issued by the Treasury with a year or less to maturity are called “Bills”; bonds issued with 1–10 years to maturity are called “notes”; and bonds issued with more than 10 years to maturity are called “bonds”. The entire category of bonds issued by a government treasury is often collectively referred to as “treasuries.” Government bonds issued by national governments may be referred to as sovereign debt.

Agency bonds are those issued by government-affiliated organizations such as Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

Varieties of Bonds

Zero-coupon bonds do not pay coupon payments and instead are issued at a discount to their par value that will generate a return once the bondholder is paid the full face value when the bond matures. U.S. Treasury bills are a zero-coupon bond.

Convertible bonds are debt instruments with an embedded option that allows bondholders to convert their debt into stock at some point, depending on certain conditions like the share price. For example, imagine a company that needs to borrow $1 million to fund a new project. They could borrow by issuing bonds with a 12% coupon that matures in 10 years. However, if they knew that there were some investors willing to buy bonds with an 8% coupon that allowed them to convert the bond into stock if the stock’s price rose above a certain value, they might prefer to issue those. The convertible bond may the best solution for the company because they would have lower interest payments while the project was in its early stages. If the investors converted their bonds, the other shareholders would be diluted, but the company would not have to pay any more interest or the principal of the bond. The investors who purchased a convertible bond may think this is a great solution because they can profit from the upside in the stock if the project is successful. They are taking more risk by accepting a lower coupon payment, but the potential reward if the bonds are converted could make that trade-off acceptable.

Callable bonds also have an embedded option but it is different than what is found in a convertible bond. A callable bond is one that can be “called” back by the company before it matures. Assume that a company has borrowed $1 million by issuing bonds with a 10% coupon that mature in 10 years. If interest rates decline (or the company’s credit rating improves) in year 5 when the company could borrow for 8%, they will call or buy the bonds back from the bondholders for the principal amount and reissue new bonds at a lower coupon rate. A callable bond is riskier for the bond buyer because the bond is more likely to be called when it is rising in value. Remember, when interest rates are falling, bond prices rise. Because of this, callable bonds are not as valuable as bonds that aren’t callable with the same maturity, credit rating, and coupon rate.

Illustration 3: A Swedish bond from 1955.

A Puttable bond allows the bondholders to put or sell the bond back to the company before it has matured. This is valuable for investors who are worried that a bond may fall in value, or if they think interest rates will rise and they want to get their principal back before the bond falls in value. The bond issuer may include a put option in the bond that benefits the bondholders in return for a lower coupon rate or just to induce the bond sellers to make the initial loan. A puttable bond usually trades at a higher value than a bond without a put option but with the same credit rating, maturity, and coupon rate because it is more valuable to the bondholders.

The possible combinations of embedded puts, calls, and convertibility rights in a bond are endless and each one is unique. There isn’t a strict standard for each of these rights and some bonds will contain more than one kind of “option” which can make comparisons difficult. Generally, individual investors rely on bond professionals to select individual bonds or bond funds that meet their investing goals.

Pricing Bonds

The market prices bonds based on their particular characteristics. A bond’s price changes on a daily basis. But there is a logic to how bonds are valued. Bonds do not have to be held to maturity. At any time, a bondholder can sell their bonds in the open market, where the price can fluctuate, sometimes dramatically.

The price of a bond changes in response to changes in interest rates in the economy. This is due to the fact that for a fixed-rate bond the issuer has promised to pay a coupon based on the face value of the bond—so for a $1,000 par, 10% annual coupon bond, the issuer will pay the bondholder $100 each year. Say that prevailing interest rates are also 10% at the time that this bond is issued, as determined by the rate on a short-term government bond. An investor would be indifferent investing in the corporate bond or the government bond since both would return $100. However, imagine a little while later, that the economy has taken a turn for the worse and interest rates dropped to 5%. Now, the investor can only receive $50 from the government bond, but would still receive $100 from the corporate bond.

This difference makes the corporate bond much more attractive. So, investors in the market will bid up to the price of the bond until it trades at a premium that equalizes the prevailing interest rate environment—in this case, the bond will trade at a price of $2,000 so that the $100 coupon represents 5%. Likewise, if interest rates soared to 15%, then an investor could make $150 from the government bond and would not pay $1,000 to earn just $100. This bond would be sold until it reached a price that equalized the yields, in this case to a price of $666.67.

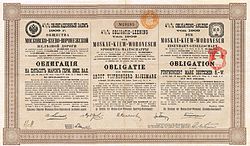

Illustration 4: Railroad obligation of the Moscow-Kiev-Voronezh railroad company, printed in Russian, Dutch and German.

Inverse to Interest Rates

This is why the famous statement that a bond’s price varies inversely with interest rates works. When interest rates go up, bond prices fall in order to have the effect of equalizing the interest rate on the bond with prevailing rates, and vice versa.

Another way of illustrating this concept is to consider what the yield on our bond would be given a price change, instead of given an interest rate change. For example, if the price were to go down from $1,000 to $800, then the yield goes up to 12.5%. This happens because you are getting the same guaranteed $100 on an asset that is worth $800 ($100/$800). Conversely, if the bond goes up in price to $1,200, the yield shrinks to 8.33% ($100/$1,200).

Bond Risk

Bonds are relatively safe investments, but just like any other investment they do come with a risk.

Interest Rate Risk: Interest rates share an inverse relationship with bonds, so when rates rise, bonds tend to fall and vice versa. Interest rate risk comes when rates change significantly from what the investor expected. If interest rates decline significantly, the investor faces the possibility of prepayment. If interest rates rise, the investor will be stuck with an instrument yielding below market rates. The greater the time to maturity, the greater the risk.

Credit or default risk is the risk that interest and principal payments due on the obligation will not be made as required. When an investor buys a bond, they expect that the issuer will make good on the interest and principal payments—just like any other creditor. When an investor looks into corporate bonds, they should weigh out the possibility that the company may default on the debt. Safety usually means the company has greater operating income and cash flow compared to its debt. If the inverse is true and the debt outweighs available cash, the investor may want to stay away.

Illustration 6: Bond certificate for the state of South Carolina issued in 1873 under the state’s Consolidation Act.

Prepayment risk is the risk that a given bond issue will be paid off earlier than expected, normally through a call provision. This can be bad news for investors because the company only has an incentive to repay the obligation early when interest rates have declined substantially. Instead of continuing to hold a high-interest investment, investors are left to reinvest funds in a lower interest rate environment.

Reinvestment risk, a bond poses a reinvestment risk to investors if the proceeds from the bond or future cash flows will need to be reinvested in a security with a lower yield than the bond originally provided. Reinvestment risk can also come with callable bonds—investments that can be called by the issuer before the maturity rate.

For example, imagine an investor buys a $1,000 bond with an annual coupon of 12%. Each year, the investor receives $120 (12% x $1,000), which can be reinvested back into another bond. But imagine that, over time, the market rate falls to 1%. Suddenly, that $120 received from the bond can only be reinvested at 1%, instead of the 12% rate of the original bond.

Another risk is that a bond will be called by its issuer. Callable bonds have call provision that allow the bond issuer to purchase the bond back from the bondholders and retire the issue. This is usually done when interest rate fall substantially since the issue date. Call provisions allow the issuer to retire the old, high-rate bonds and sell low-rate bonds in a bid to lower debt costs.

Default risk occurs when the bond’s issuer is unable to pay the contractual interest or principal on the bond in a timely manner or at all. Credit rating services give credit ratings to bond issues. For example, most federal governments have very high credit ratings (AAA). However, small emerging companies have some of the worst credit—BB and lower—and are more likely to default on their bond payments. In these cases, bondholders will likely lose all or most of their investments.

Inflation Risk- This risk refers to situations when the rate of price increases in the economy deteriorates the returns associated with the bond. This has the greatest effect on fixed bonds, which have a set interest rate from inception.

How to buy a bond

Bond Broker- Many specialized bond brokerages require high minimum initial deposits; $5,000 is typical. There may also be account maintenance fees. And of course, commissions on trades. Depending on the quantity and type of bond purchased, broker commissions can range from 0.5% to 2%. When using a broker (even your regular one) to purchase bonds, you may be told that the trade is free of commison. What often happens, however, is that the price is marked up so that the cost you are charged essentially includes a compensatory fee. If the broker isn’t earning anything off of the transaction, he or she probably would not offer the service. For example, say you placed an order for 10 corporate bonds that were trading at $1,025 per bond. You’d be told, though, that they cost $1,035.25 per bond, so the total price of your investment comes not to $10,250 but to $10,352.50. The difference represents an effective 1% commission for the broker. To determine the markup before purchase, look up the latest quote for the bond; you can also use the TRACE, which shows all over-the-counter (OTC) transactions for the secondary bond market. Use your discretion to decide whether or not the commission fee is excessive or one you are willing to accept.

Buying Government Bonds-Purchasing government bonds such as Treasuries (U.S.) or Canada Savings Bonds (Canada) works slightly differently than buying corporate or municipal bonds. Many financial institutions provide services to their clients that allow them to purchase government bonds through their regular investment accounts. If this service is not available to you through your bank or brokerage, you also have the option to purchase these securities directly from the government.

Illustration 7: A USA Bond issuance

Bond Funds- Another way to gain exposure in bonds would be to invest in a bond fund, a mutual fund or ETF, that exclusively holds bonds in its portfolio. These funds are convenient since they are usually low-cost and contain a broad base of diversified bonds so you don’t need to do your research to identify specific issues. When buying and selling these funds (or, for that matter, bonds themselves on the open market), keep in mind that these are “secondary market” transactions, meaning that you are buying from another investor and not directly from the issuer. One drawback of mutual funds and ETFs is that investors do not know the maturity of all the bonds in the fund portfolio since they are changing quite often, and therefore these investment vehicles are not appropriate for an investor who wishes to hold a bond until maturity. Another drawback is that you will have to pay additional fees to the portfolio managers, though bond funds tend to have lower expense ratios than their equity counterparts. Passively managed bond ETFs, which track a bond index, tend to have the fewest expenses of all. Bond ETFs pay out interest through a monthly dividend, while any capital gains are paid out through an annual dividend. Bond ETFs offer many of the same features of an individual bond, including a regular coupon payment. One of the most significant benefits of owning bonds is the chance to receive fixed payments on a regular schedule. These payments traditionally happen every six months. Bond ETFs, in contrast, hold assets with different maturity dates, so at any given time, some bonds in the portfolio may be due for a coupon payment. For this reason, bond ETFs pay interest each month with the value of the coupon varying from month to month.

Assets in the fund are continually changing and do not mature. Instead, bonds are bought and sold as they expire or exit the target age range of the fund. The suppliers of bond ETFs get around the liquidity problem by using representative sampling, which simply means tracking only a sufficient number of bonds to represent an index. Since a bond ETF never matures, there isn’t a guarantee the principal will be repaid in full.

Common Bond-Buying mistakes

1. Ignoring Interest Rate Moves

Interest rates and bond prices have an inverse relationship. As rates go up, bond prices decline, and vice versa. This means that in the period before a bond’s redemption on its maturity date. the price of the issue will vary widely as interest rates fluctuate. Many investors don’t realize this.

2. Not Noting the Claim Status

Not all bonds are created equal. There are senior notes, which are often backed by collateral (such as equipment) that are given the first claim to company asset in case of bankruptcy and liquidation. There are also subordinate debentures, which still rank ahead of common stock in terms of claim preference, but below that of the senior debt holder. It is important to understand which type of debt you own, especially if the issue you are buying is in any way speculative.

In the event of bankruptcy, bond investors have the first claim to a company’s assets. In other words, at least theoretically, they have a better chance of being made whole if the underlying company goes out of business. To determine what type of bond you own, check the certificate if possible. It will likely say the words “senior note,” or indicate the bond’s status in some other fashion on the document. Alternatively, the broker that sold you the note should be able to provide that information. If the bond is an initial issue the investor can look at the underlying company’s financial documents, such as the 10-K or the prospect.

3. Assuming a Company is Sound

Just because you own a bond or because it is highly regarded in the investment community doesn’t guarantee that you will earn a dividend payment, or that you will ever see the bond redeemed. In many ways, investors seem to take this process for granted.

But rather than make the assumption that the investment is sound, the investor should review the company’s financials and look for any reason it won’t be able to service its obligation.

They should look closely at the income statement and then take the annual net income figure and add back taxes, depreciation, and any other non-cash charges. This will help you to determine how many times that figure exceeds the annual debt service number. Ideally, there should be at least two times coverage in order to feel comfortable that the company will have the ability to pay down its debt.

4. Misjudging Market Perception

As mentioned above, bond prices can and do fluctuate. One of the biggest sources of volatility is the market’s perception of the issue and the issuer. If other investors don’t like the issue or think the company won’t be able to meet its obligations, or if the issuer suffers a blow to its reputation, the price of the bond will decrease in value. The opposite is true if Wall Street views the issuer or the issue favorably.

A good tip for bond investors is to take a look at the issuer’s common stock to see how it is being perceived. If it is disliked, or there is unfavorable research in the public domain on the equity, it will likely spill over and be reflected in the price of the bond as well.

5. Failing to Check the History

It is important for an investor to look over old annual reports and review a company’s past performance to determine whether it has a history of reporting consistent earnings. Verify that the company has made all interest, tax, and pension plan obligation payments in the past.

Specifically, a potential investor should read the company’s management discussion and analysis (MD&A) section for this information. Also, read the proxy statement—it, too, will yield clues about any problems or a company’s past inability to make payments. It may also indicate future risks that could have an adverse impact on a company’s ability to meet its obligations or service its debt.

The goal of this homework is to gain some level of comfort that the bond you are holding isn’t some type of experiment. In other words, check that the company has paid its debts in the past and, based upon its past and expected future earnings is likely to do so in the future.

Illustration 8; Pacific Railroad Bond issued by City and County of San Francisco, CA. May 1, 1865

6. Ignoring Inflation Trends

When bond investors hear reports of inflation trends, they need to pay attention. Inflation can eat away a fixed income investor’s future purchasing power quite easily.

For example, if inflation is growing at an annual rate of four percent, this means that each year it will take a four percent greater return to maintain the same purchasing power. This is important, particularly for investors that buy bonds at or below the rate of inflation, because they are actually guaranteeing they’ll lose money when they purchase the security.

Of course, this is not to say that an investor shouldn’t buy a low-yielding bond from a highly-rated corporation. But investors should understand that in order to defend against inflation, they must obtain a higher rate of return from other investments in their portfolio such as common stocks or high-yielding bonds.

7. Failing to Check Liquidity

Financial publications, market data/quote services, brokers and a company’s website may provide information about the liquidity of the issue you hold. More specifically, one of these sources may yield information about what type of volume the bond trades on a daily basis.

This is important because bondholders need to know that if they want to dispose of their position, adequate liquidity will ensure that there will be buyers in the market ready to assume it. Generally speaking, the stocks and bonds of large, well-financed companies tend to be more liquid than those of smaller companies. The reason for this is simple — larger companies are perceived as having a greater ability to repay their debts.

Warren Buffett:

tlover tonet

I’ve been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this information So i am happy to convey that I have an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make sure to don’t forget this web site and give it a glance regularly.