Introduction

South Korea, officially known as the Republic of Korea (ROK), presents an intriguing case study in economic development. From the ravages of the Korean War to becoming an economic powerhouse, the South Korean economy’s journey is a testament to a combination of strategic planning, relentless hard work, and innovative spirit.

From its humble beginning the countries economy had grown to a nominal GDP of ₩2.24 quadrillion (US$1.72 trillion) making it the 4th largest economy in Asia and the 12th largest in the world

Part of the OECD and the G20. South Korea’s education system and an educated and motivated population was largely responsible for the technology boom and economic development in the country. South Korea adapted an export-oriented economic strategy to fuel its economy. In 2019, South Korea was the eight largest exporter and eight largest importer in the world.

Financial organizations, such as the international monetary fund comments that the South Korean economy is resilient against various economic crises. They country’s economic advantages such as its low state debt, and high fiscal reserves and its country’s major economic output being the technology products exports is the reason behind this resilience.

However, despite the South Korean economy’s high growth and structural stability, the credit rating of the country is damaged in the stock market due to North Korea in times of military crisis. The recurring conflict affects the financial markets of its economy

Historical Background

The Beginning

The foundation of the South Korean economic story is deeply rooted in its tumultuous history. After gaining independence from Japan in 1945, Korea was split into North and South. The Korean War (1950-1953) devastated the South Korean economy, leaving it as one of the poorest countries in the world.

However, South Korea only remained a country with less developed markets for a little more than a decade after the Korean war.

The principal reason behind the growth of the South Korea’s economic development is the industrial sector. Due to strong domestic encouragement and some foreign aid, Seoul’s industrialists introduced modern technologies into outmoded or newly built facilities, increased the production of commodities especially those for sale in foreign markets and invested the proceeds back into further industrial expansion. As a result, industry altered South Korea’s landscape, drawing millions of labourers to urban manufacturing centres.

The Miracle on the Han River

In the beginning in the 1960s, under the leadership of Park Chung-hee, South Korea underwent rapid industrialization and modernization, an era often referred to as the “Miracle on the Han River.”

The government instituted comprehensive reforms and laid the groundwork for an export-driven economy. To promote development, a policy of export oriented industrialization was applied, closing the entry into the country of all kinds of foreign products, except raw materials. Major industries, such as steel, shipbuilding, and chemicals, were heavily promoted. Infrastructure, education, and R&D became vital investment areas.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of family-controlled conglomerates, or “chaebols,” like Samsung, Hyundai, and LG. Their growth was often backed by government policies, and they became significant players in driving South Korea’s economic expansion.

Through the model of export-led industrialization, the government incentigvized corporations to develop new technology and upgrade productive efficiency to compete the global market. By adhering to state regulations and demands, firms were awarded subsidization and investment support to develop their export markets in the evolving international arena. The chaebols received state incentives such as tax breaks, legality for their exploitation system and cheap or free financing In addition, the inflow of foreign capital was encouraged to supplement the shortage of domestic savings. These efforts enabled South Korea to achieve growth in exports and subsequent increases in income.

By emphasizing the industrial sector, Seoul’s export-oriented development strategy left the rural sector barely touched. The steel and shipbuilding industries in particular played key roles in developing South Korea’s economy during this time.

The Asian financial crisis and its aftermath

In 1997, South Korea, along with many Asian nations, faced a severe financial crisis. The chaebols’ excessive borrowing and a fixed exchange rate regime were among the primary reasons for South Korea’s vulnerability. The crisis led to significant economic restructuring, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) providing a $58 billion bailout package.

Hosting the 1988 Summer Olympic Games, commonly known as Seoul 1988, provided the country with the momentum to join the ranks of semi-advanced countries. The overseas mass media called South Korea one of the four Asian tigers along with Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong. In December 1996, the country became the 29th member country of the OECD, which is largely composed of advanced countries.

In response, the South Korean government implemented stringent reforms, including financial sector liberalization, corporate governance reforms, and the restructuring of chaebols. By 2001, the country had remarkably bounced back, with its economy growing at 4%.

High-tech industries in the 1990s and 2000s

In 1990, South Korean manufacturers planned a shift in future production toward high-technology industries. In June 1989, panels of government officials, scholars, and business leaders held planning sessions on the production of such goods as new materials, mechatronics, bioengineering, microelectronics, fine chemistry, and aerospace.

This shift did not mean an immediate decline in heavy industries such as automobile and ship production, which had dominated the economy in the 1980s.

In November 1997, a foreign exchange crisis hit the country, forcing it to turn to the IMF for a bailout. It was the first ordeal the country had to confront after years of rapid economic growth. The country took the drastic step to drive insolvent businesses out of the market and then pushed ahead with industrial restructuring. In only two years, the country regained its previous growth rate and price levels as well as a current account balance surplus. In the process, some 3.5 million people joined in the campaign to collect gold to help the government repay the fund borrowed from the IMF. A total of 227 tons of gold were collected. The world marveled at the South Koran people’s voluntary participation in the determined effort to repay its national debts

South Korea today is known as a Launchpad of a mature mobile market, where developers thrive in a market where few technology constraints exist. There is a growing trend of inventions of new types of media or apps, using the 4G and 5G internet infrastructure in South Korea. South Korea has today the infrastructures to meet a density of population and culture that has the capability to create strong local particularity. The country has displayed global competitiveness in various fields such as mobile phones, semiconductors, automobiles, chemicals, and steelmaking. In recent years, its cultural content, including music, gaming, and webtoons, is emerging as an essential industry in itself, taking the lead in the Korean economy.

Chaebols- The untouchable families of South Korea

The chaebols are large family-owned business conglomerates that dominate South Korea’s economic, political, and social life. Their roots trace back to the 1960s and 70s when South Korea, under the leadership of then-president Park Chung-hee, embarked on an ambitious plan of industrialization. The government formed strategic partnerships with select business groups, offering them financial incentives, cheap loans, and protection from competition in exchange for their commitment to the national industrialization effort.

At the heart of every chaebol is a founding family. The typical culture at one of these conglomerates is highly paternalistic. Much of the environment is defined by the chairman who acts as a “fatherly figure” to his subordinates. Workers commit to long hours, most notably on weekends and holidays, to appease their superiors. Company outings and drinking sessions tend to be compulsory to foster a sense of family and belonging among employees. Employers believe that enhancing a common bond between them would translate into prosperity and productivity for the company. Other practices that would be uncommon for Western workplaces to engage in include gift-giving to employees and arranging dates for workers in search of relationships or marriage.

Chaebols are notoriously hierarchical. As such, it is unusual for an individual to challenge or question the decision-making of his or her boss. Promotion is rarely merit-based. Rather, it is through the order of age and time served to the conglomerate. If a worker does not attain an executive or senior-management role by the age of fifty, he or she is commonly forced to resign.

Because of South Korea’s long-lasting relationship with chaebols, South Korea has always suppressed and ignored labour unions. As of 2019, there are only two legally recognized labour unions in South Korea: The Federation of Korean Trade Unions and the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions. Despite these unions’ attempts at reform, the South Korean government does not take many actions. If a union oversteps and openly criticizes a chaebol, it faces serious repercussions, as chaebols are essentially government entities. It is well known that chaebols evade taxes regularly.

Many South Korean family-run chaebols have been criticized for low dividend payouts and other governance practices that favor controlling shareholders at the expense of ordinary investors. Because of their major role in the Korean stock market, foreign investors play a massive part in whether or not chaebol conglomerates remain financially successful.

Foreign investors tend to avoid chaebols, especially those that displayed heavy political influence in South Korea, like Samsung and Hyundai. Investors are reluctant to invest in large control-ownership disparity businesses because these companies tended to cheat shareholders to have higher personal financial gain. A study published in the Journal of the Japanese and International Economies found that after the 1997 Asian financial crisis, foreign investment behavioural patterns changed drastically. While foreign investors like to hold shares in large companies with high profit and liquidity margins, they do not show any particular interest in either chaebol or non-chaebol companies. Nonetheless, chaebols are still able to survive, highlighting just how much power and aid they receive from the Korean government. All but 3 of the top 50 firms listed on the Korean Stock Exchange are designated as chaebols, and despite chaebols only accounting for just over 10 percent of the country’s workers, the four largest chaebols hold 70 percent of total market capitalization, and all chaebols together holding 77 percent as of the late 2010s.

Even though they might hold a minor stake in terms of shares, they exercise considerable control through a complex web of cross-shareholdings among subsidiary companies. One of the characteristics of a Chaebols is diversification meaning have a diverse range of businesses. For instance, Samsung, initially a trading company, has expanded into electronics, shipbuilding, construction, insurance. Many chaebols are known for vertical integration. They often control the entire supply chain, from raw materials to finished products, ensuring reduced costs and greater markert.

While chaebols have been instrumental in South Korea’s economic success, they haven’t been without controversies. The power and wealth concentrated in a few chaebols have sometimes stymied the growth of small and medium-sized businesses. Due to their complex structures and family dominance, issues of corporate governance, transparency, and fair trade practices have been raised. Over the years, several chaebols have been embroiled in political scandals, raising concerns about their influence on political decisions. For many people the nut rage incident where Korean Air vice president Heather Cho dissatisfied with the way a flight attendant served nuts on the plane, ordered the aircraft to return to the gate before takeoff , highlights the power chaebols have.

Economic Inequality in South Korea

Economic inequality, a universal challenge, has emerged as a focal point of discussion in South Korea, a nation renowned for its remarkable post-war economic transformation. While the “Miracle on the Han River” narrates a story of astounding growth, there’s a less talked about subplot – widening economic disparities.

South Korea was the 5th most equal country in the world in 2019, however economic inequality is growing. According to data from 2010, low-income earners (those earning 12 million won or less) make up 37.8% of South Korea’s labour force. However, among other countries in OECD, South Korea performs relatively well when considering indicators such as the Gini coefficient and Palma ratio, especially when limiting the comparison to countries with similar populations

Income disparity in South Korea has been growing. The top 10% of income earners in the country make around 45% more than the bottom 10%. The implications of this gap manifest in various ways, from access to quality education and healthcare to overall life satisfaction and social mobility.

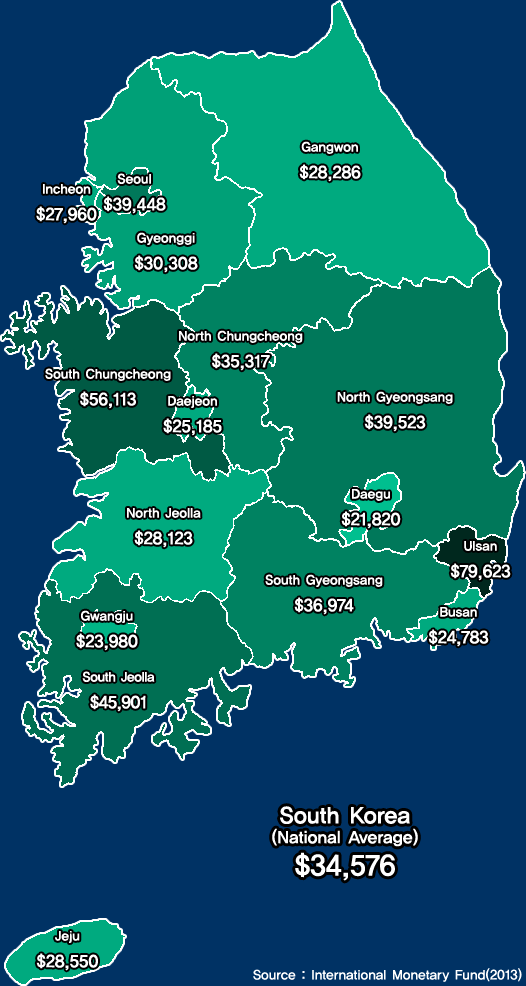

Regional disparities also exists in South Korea. Seoul and its neighboring regions, being the epicenters of commerce and industry, have seen greater growth than other parts of the country, leading to noticeable regional economic imbalances.

Figure above shows regional disparities in South Korea.

There is a generation gap in South Korea. Young South Koreans, despite being more educated than previous generations, face challenges like underemployment, precarious job security, and rising housing costs. On the other hand, the elderly population, which has grown due to increased life expectancy, faces poverty rates that are alarmingly high by OECD standards. The social safety net in South Korea is less comprehensive than in many other developed nations. This has particularly affected the elderly population, leading to high levels of elderly poverty.

Real estate in South Korea, especially in Seoul, has seen skyrocketing prices, making homeownership an unattainable dream for many young people. Speculative investments in property have further exacerbated this issue. Economic inequality is often linked to low or limited social mobility, a situation which may instill a sense of hopelessness among South Korea’s youth. Gambling, though extremely limited due to its legality in South Korea, can be a dangerous source of debt for South Koreans who are susceptible to gambling and gambling addiction. In 2017, the availability of cryptocurrency in South Korea,combined with a lack of legal outlets for gambling, has contributed to gambling problems and associated deb

South Korea’s labor market is characterized by a divide between regular and non-regular workers. Non-regular workers, despite making up a substantial portion of the workforce, face lower wages, less job security, and fewer benefits.

Important Sectors of the South Korean Economy

Overall GDP by section can be summarized as agriculture: 2.2%industry: 39.3%services: 58.3%(2017 est.)

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding-During the 1970s and 1980s, South Korea became a leading producer of ships, including oil supertankers, and oil-drilling platforms. The country’s major shipbuilder was Hyundai, which built a 1-million-ton capacity drydock at Ulsan in the mid-1970s. Daewoo joined the shipbuilding industry in 1980 and finished a 1.2-million-ton facility at Okpo on Geoje Island, south of Busan, in mid-1981.

The industry declined in the mid-1980s because of the oil glut and because of a worldwide recession. There was a sharp decrease in new orders in the late 1980s; new orders for 1988 totaled 3 million gross tons valued at US$1.9 billion, decreases from the previous year of 17.8 percent and 4.4 percent, respectively. These declines were caused by labor unrest, Seoul’s unwillingness to provide financial assistance, and Tokyo’s new low-interest export financing in support of Japanese shipbuilders. However, the South Korean shipping industry was expected to expand in the early 1990s because older ships in world fleets needed replacing. South Korea eventually became the world’s dominant shipbuilder with a 50.6% share of the global shipbuilding market as of 2008. Notable Korean shipbuilders are Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, and the now bankrupt STX Offshore & Shipbuilding.

Electronics

Electronics is one of South Korea’s main industries. During the 1980s through the 2000s, South Korean companies such as Samsung, LG and SK led South Korea’s growth. In 2017, 17.1% of South Korea’s exports were semiconductors produced by Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix. Samsung and

LG are also major producers in electronic devices such as televisions, smartphones, display, and computers.

Automobiles

The automobile industry was one of South Korea’s major growth and export industries in the 1980s. By the late 1980s, the capacity of the South Korean motor industry had increased more than fivefold since 1984; it exceeded 1 million units in 1988. Total investment in car and car-component manufacturing was over US$3 billion in 1989. In 1988 automobile exports totaled 576,134 units, of which 480,119 units (83.3 percent) were sent to the United States.

Throughout most of the late 1980s, much of the growth of South Korea’s automobile industry was the result of a surge in exports; 1989 exports, however, declined 28.5 percent from 1988. This decline reflected sluggish car sales to the United States, especially at the less expensive end of the market, and labor strife at home. South Korea today has developed into one of the world’s largest automobile producers. The Hyundai Kia Automotive Group is South Korea’s largest automaker in terms of revenue, production units and worldwide presence.

Mining

Most of the mineral deposits in the Korean Peninsula are located in North Korea, with the South only possessing an abundance of tungsten and graphite. Coal, iron ore, and molybdenum are found in South Korea, but not in large quantities and mining operations are on a small scale. Much of South Korea’s minerals and ore are imported from other countries. Most South Korean coal is anthracite that is only used for heating homes and boilers.

In 2019, South Korea was the 3rd largest world producer of bismuth, the 4th largest world producer of rhenium, and the 10th largest world producer of sulfur.

Construction

Construction has been an important South Korean export industry since the early 1960s and remains a critical source of foreign currency and invisible export earnings. By 1981 overseas construction projects, most of them in the Middle East, accounted for 60 percent of the work undertaken by South Korean construction companies.

South Korean construction companies concentrated on the rapidly growing domestic market in the late 1980s. By 1989 there were signs of a revival of the overseas construction market: the Dong Ah Construction Company signed a US$5.3 billion contract with Libya to build the second phase of Libya’s Great Man-Made River Project, with a projected cost of US$27 billion when all 5 phases were completed. South Korean construction companies signed over US$7 billion of overseas contracts in 1989. Korea’s largest construction companies include Samsung C&T Corporation, which built some of the highest building’s and most noteworthy skyscrapers such as three consecutively world’s tallest buildings: Petronas Towers, Taipei 101, and Burj Khalifa.

Armaments

Since the 1980s, South Korea has begun exporting military equipment and technology to boost its international trade. South Korea also exports various core components of other countries’ advanced military hardware. Those hardware include modern aircraft such as F-15K fighters and AH-64 attack helicopters which will be used by Singapore. In other major outsourcing and joint-production deals, South Korea has jointly produced the S-300 air defense system of Russia via Samsung Group. South Korea’s defense exports were $1.03 billion in 2008 and $1.17 billion in 2009

Tourism

In 2012, 11.1 million foreign tourists visited South Korea, making it one of the most visited countries in the world, up from 8.5 million in 2010. Many tourists from all around Asia visit South Korea which has been due to the rise of Korean Wave (Hallyu).Seoul is the principal tourist destination for visitors; popular tourist destinations outside of Seoul include Seorak-san national park, the historic city of Gyeongju and semi-tropical Jeju Island.

Overall

South Korea relies upon exports to fuel the growth of its economy, with finished products such as electronics, textiles, ships, automobiles, and steel being some of its most important exports. Although the import market has liberalized in recent years, the agricultural market has remained protectionist due to disparities in the price of domestic agricultural products such as rice with the international market. As of 2005, the price of rice in South Korea was four times that of the average price of rice on the international market, and it was believed that opening the agricultural market would affect South Korean agricultural sector negatively. In late 2004, however, an agreement was reached with the WTO in which South Korean rice imports will gradually increase from 4% to 8% of consumption by 2014. In addition, up to 30% of imported rice will be made available directly to consumers by 2010, where previously imported rice was only used for processed foods. Following 2014, the South Korean rice market will be fully opened

South Korea established an export-oriented economic structure centered on large businesses while pursuing growth in the face of insufficient capital and resources. This led conglomerates to dominate industry, making the economic structure heavily reliant on exports and imports, thus leaving the country susceptible to external economic conditions.

Most Exported goods are : Integrated Circuits 15.35%, Machinery 12.81%, Vehicles and their parts 11.34%, Mineral Fuels 7.01%, Plastics 5.86%, Iron and Steel 4.23%, Instruments and Apparatus 4.16%, Organic Chemicals 3.85%, Others 35.39%(2019 estm.)

Characteristics of the South Korean Economy

Export-driven: South Korea is the 10th largest exporter in the world. Major exports include semiconductors, petrochemicals, automobiles, and ships. Its ability to innovate and adapt to global market needs has been a significant factor in its export success.

Innovation and Technology: South Korea is a global leader in various high-tech industries. The country boasts the world’s highest broadband penetration, and its firms lead in sectors like mobile technology, semiconductors, and OLED display production.

Chaebols: These conglomerates still play a dominant role in the South Korean economy. While they have been catalysts for growth, they also raise concerns related to corporate governance, competition, and economic disparity.

Education: South Koreans place a high emphasis on education, resulting in a highly skilled and competitive workforce. The country consistently ranks high in global education indices.

Challenges facing the South Korean Economy

Demographics: South Korea has one of the world’s lowest fertility rates. A rapidly aging population puts a strain on the social security system and can lead to potential labor shortages.

Dependency on Exports: While exports have driven growth, over-dependency makes the economy vulnerable to global market fluctuations.

Inter-Korean Relations: Political and military tensions with North Korea have implications for investor confidence and regional stability.

Corporate Governance: While reforms post the 1997 crisis have been implemented, there are still concerns about transparency and accountability within the chaebols.

Challenges also include an aging population, low worker productivity, and the need to implement a structural shift away from overreliance on export-led growth and expansionary fiscal policy.

Conclusion

South Korea’s economic transformation over the past six decades is nothing short of miraculous. A mix of strategic state interventions, entrepreneurial spirit, cultural emphasis on education, and adaptability has propelled the country into the ranks of advanced economies. However, as with all nations, South Korea faces challenges that it must address to ensure continued prosperity. With its track record of overcoming adversity, the South Korean economy’s future remains promising.

Main Export and Import partners of South Korea

| Country/Region | Export (M$) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 162,125 | 26.8% | |

| 72,720 | 12.0% | |

| 48,622 | 8.0% | |

| 45,996 | 7.6% | |

| 30,529 | 5.1% | |

| 20,872 | 3.4% | |

| 20,784 | 3.2% | |

| 15,606 | 2.6% | |

| 12,037 | 2.0% | |

| 11,782 | 2.0% | |

| 11,458 | 1.9% | |

| Others | 173,201 | 28.6% |

| Total | 604,860 | 100.0% |

| Country/Region | Import (M$) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 106,489 | 19.9% | |

| 58,868 | 11.0% | |

| 54,604 | 10.2% | |

| 26,336 | 4.9% | |

| 20,854 | 3.9% | |

| 20,719 | 3.9% | |

| 19,643 | 3.7% | |

| 17,504 | 3.4% | |

| 16,738 | 3.1% | |

| 16,294 | 3.0% | |

| 12,762 | 2.0% | |

| Others | 177,153 | 33.1% |

| Total | 535,202 | 100.0% |