Introduction

Norway, known for its breathtaking fjords and robust welfare state, also boasts one of the most prosperous economies in the world. This Scandinavian nation, with a population of just over 5.4 million has managed to create a high standard of living and an economic model that is often envied globally. The economy of Norway is a highly developed mixed economy with state-ownership in strategic areas and is ranked 30th in total GDP with a top credit rating of AAA. Although sensitive to global business cycles, the economy of Norway has shown robust growth since the start of the industrial era. This article will explore the various aspects of Norway’s economy, from its historical development and key sectors to challenges and future prospects.

Figure 1: The flag of Norway

Historical Development of the Norwegian Economy

- Pre Industrial History

Norway’s economy has undergone significant transformations over the centuries. In the early stages of its history, Norway’s economy was primarily agrarian, with fishing, forestry and agriculture as the main sources of livelihood. The rugged terrain and harsh climate limited large-scale agriculture, making fishing a vital industry. Norway’s extensive coastline, abundant with marine life, allowed fishing to become a cornerstone of the economy, especially in coastal communities.

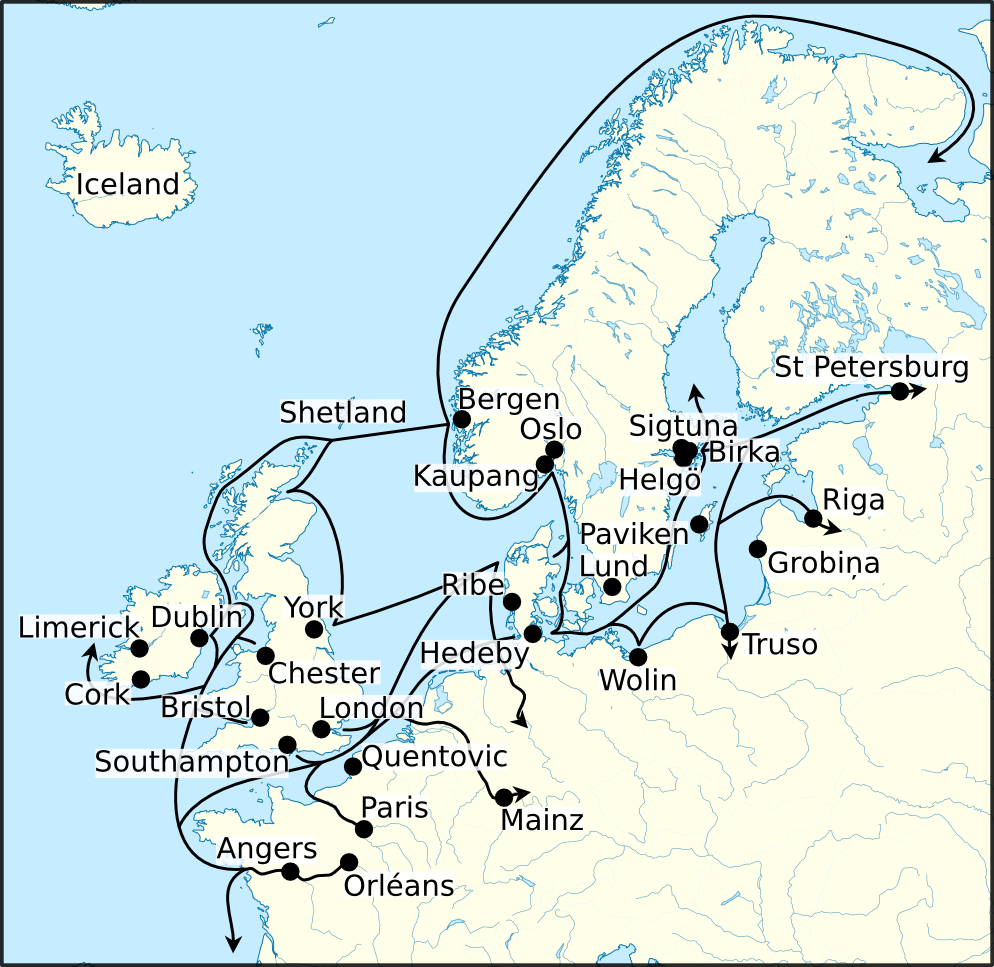

Figure 2: Trade routes during the Viking Age

The Viking Age, spanning from the late 8th to early 11th century, also played a role in shaping the early Norwegian economy. The Vikings were not only raiders but also traders who established trade routes across Europe. Their expeditions brought wealth to Norway, though this period did not lead to significant economic development in the modern sense. Prior to the industrial revolution, Norway’s economy was largely based on agriculture, timber, and fishing. Norwegians typically lived under conditions of considerable scarcity, though famine was rare.

- Industrialization and Economic diversification

The 19th century marked a period of industrialization in Norway. The discovery of rich natural resources, such as timber, water for hydroelectric power, and minerals, provided the impetus for economic growth. The country began to develop its infrastructure, with the construction of railways, roads, and ports facilitating trade and industry.Aside from mining in Kongsberg, Røros and Løkken, industrialization came with the first textile mills that were built in Norway in the middle of the 19th century. But the first large industrial enterprises came into formation when entrepreneurs’ politics led to the founding of banks to serve those needs.

Figure 3: Kongsberg Mine

Industries also offered employment for a large number of individuals who were displaced from the agricultural sector. As wages from industry exceeded those from agriculture, the shift started a long-term trend of reduction in cultivated land and rural population patterns. The working class became a distinct phenomenon in Norway, with its own neighborhoods, culture, and politics.

After World War II, the Norwegian Labour Party, with Einar Gerhardsen as prime minister, embarked on a number of social democratic reforms aimed at flattening the income distribution, eliminating poverty, ensuring social services such as retirement, medical care, and disability benefits to all, and putting more of the capital into the public trust.

Highly progressive income taxes, the introduction of value-added tax, and a wide variety of special surcharges and taxes made Norway one of the most heavily taxed economies in the world. Authorities particularly taxed discretionary spending, levying special taxes on automobiles, tobacco, alcohol, cosmetics, etc.

The shipping industry, in particular, became a vital part of Norway’s economy. By the early 20th century, Norway had one of the largest merchant fleets in the world. This industry was supported by Norway’s strategic location and its expertise in shipbuilding and navigation. The export of timber, fish, and later, manufactured goods, contributed significantly to the nation’s wealth.

- Oil Boom and Economic Transformation

The most significant turning point in Norway’s economic history came in the late 1960s with the discovery of oil and natural gas in the North Sea. The first commercial oil discovery was made at the Ekofisk field in 1969, and production began in 1971. This marked the beginning of Norway’s transformation into one of the world’s leading oil exporters.

Figure 4: Oil field in the North Sea

Norway decided to stay out of OPEC keeping its own energy prices in line with world markets. The Norwegian government established its own oil company, Statoil (now known as Equinor), and awarded drilling and production rights to Norsk Hydro and the newly formed Saga Petroleum. Petroleum exports are taxed at a marginal rate of 78% (standard corporate tax of 24%, and a special petroleum tax of 54%). The North Sea turned out to present many technological challenges for production and exploration, and Norwegian companies invested in building capabilities to meet these challenges. A number of engineering and construction companies emerged from the remnants of the largely lost shipbuilding industry, creating centers of competence

Figure 5: The partly state owned Norwegian Oil company Equinor (formerly statoil) is the largest Norwegian company and one of the largest oil companies in the world.

The oil boom brought unprecedented wealth to Norway, allowing the country to build a robust welfare state and invest in infrastructure and education. The Norwegian government, however, was cautious in its approach to managing oil wealth. In 1990, the Government Pension Fund Global (often referred to as the Oil Fund) was established to manage the revenues from oil production. The fund, now one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, is designed to ensure that oil wealth benefits future generations and stabilizes the economy against fluctuations in oil prices.

- Post-Industrial economic developments

Norway is among the most expensive countries in the world, as reflected in the Big Mac Index and other indices. Historically, transportation costs and barriers to free trade had caused the disparity, but in recent years, Norwegian policy in labor relations, taxation, and other areas have contributed significantly.

The high cost of labor and other structural features of the Norwegian environment have caused concern about Norway’s ability to maintain its standard of living in a post-petroleum era. There is a clear trend toward ending the practice of “protecting” certain industries and making more of them “exposed to competition” . In addition to interest in information technology, a number of small- to medium-sized companies have been formed to develop and market highly specialized technology solutions.

Figure 6: A Norwegian cabin.

The future of the welfae state. Since World War II, successive Norwegian governments have sought to broaden and extend public benefits to its citizens, in the form of sickness and disability benefits, minimum guaranteed pensions, heavily subsidized or free universal health care, unemployment insurance, and so on. Public policy still favors the provision of such benefits, but there is increasing debate on making them more equitable and needs-based.

The primary purpose of the Norwegian tax system has been to raise revenue for public expenditures; but it is also viewed as a means to achieve social objectives, such as redistribution of income, reduction in alcohol and tobacco consumption, and as a disincentive against certain behaviors.

Key Sectors of the Norwegian Economy

Norway’s economy is characterized by a diverse range of industries, with oil and gas, shipping, fisheries, and technology playing key roles.

- Oil and Gas

The oil and gas sector is the most significant contributor to Norway’s economy. Norway is one of the largest producers of oil and natural gas in Europe and a significant exporter to global markets. The North Sea, Norwegian Sea, and Barents Sea are the primary areas of oil and gas production, with companies like Equinor (formerly Statoil) leading the industry.

Norway’s government plays a significant role in the oil sector through ownership stakes in major companies and a regulatory framework that ensures a large portion of profits benefits the state. The sector has not only brought wealth to Norway but has also fostered technological innovation and expertise in offshore drilling and exploration.

However, the dominance of the oil sector also presents challenges, particularly in the context of global efforts to combat climate change. Norway faces the difficult task of balancing its role as a major oil producer with its commitment to reducing carbon emissions and transitioning to a more sustainable economy.

- Shipping and Maritime Industry

Norway’s maritime industry is another cornerstone of its economy. The country has a long history of maritime trade, and its shipping industry is among the most advanced in the world. Norwegian companies are leaders in shipbuilding, maritime technology, and offshore services.

Figure 7: A container ship in the North Sea

The Norwegian shipping fleet is one of the most modern and efficient globally, with a focus on sustainability and reducing emissions. Norway is also a leader in maritime finance and insurance, with Oslo serving as a key hub for these industries.

The maritime sector is closely linked to the oil and gas industry, with a significant portion of the fleet dedicated to offshore support vessels, drilling rigs, and transportation of oil and gas. The industry has also diversified into sectors such as aquaculture and renewable energy, with Norwegian companies playing a key role in developing offshore wind farms.

- Fishing and Aquaculture

Fishing has been a vital part of Norway’s economy for centuries, and today, the country is one of the world’s largest exporters of fish and seafood. The rich waters surrounding Norway are home to a diverse range of fish species, including cod, salmon, and herring.

Norway’s fisheries are among the most sustainably managed in the world, with strict regulations in place to prevent overfishing and protect marine ecosystems. The country has also become a global leader in aquaculture, particularly in salmon farming. Norwegian salmon is exported to markets worldwide, making it a significant contributor to the economy.

Figure 8: A Norwegian Salmon. Norway is famous for its salmon.

The aquaculture industry has faced challenges, including concerns about environmental impact and fish health, but it continues to be a major growth sector. Norway’s expertise in sustainable fishing and aquaculture has also positioned it as a leader in global discussions on sustainable seafood production.

- Technology and Innovation

While Norway’s economy has traditionally been dominated by natural resources, the country has made significant strides in developing its technology and innovation sectors. The government has invested heavily in education, research, and development, fostering a strong environment for startups and tech companies.

Norway is particularly strong in areas such as renewable energy, telecommunications, and biotechnology. In June 2007, the government contributed to the formation of the Oslo Cancer Cluster (OCC) as a center of expertise, capitalizing on the fact that 80% of cancer research in Norway takes place in proximity to Oslo and that most Norwegian biotechnology companies are focused on cancer. The country’s expertise in offshore technology, developed through the oil and gas industry, has also been applied to renewable energy projects, including offshore wind and tidal energy.

The technology sector is seen as a key area for future economic growth, particularly as Norway seeks to diversify its economy away from oil and gas. The government has implemented policies to encourage innovation, including tax incentives, grants, and support for research and development.

- Renewable Energy

Norway is a global leader in renewable energy, particularly in hydropower, which accounts for over 90% of the country’s electricity production. The country’s abundant rivers and waterfalls provide a reliable source of clean energy, making Norway one of the most sustainable energy producers in the world.

Figure 9: Rånåsfoss hydroelectric plant in Akershus, Norway.

In recent years, Norway has also invested in other forms of renewable energy, including wind and solar power. The government’s commitment to reducing carbon emissions and transitioning to a low-carbon economy has driven these efforts, with ambitious targets set for the expansion of renewable energy capacity.

Figure 10: Norwegian off-shore wind farms.

Norway’s expertise in renewable energy technology, particularly in offshore wind, has also become a significant export industry. Norwegian companies are involved in renewable energy projects worldwide, contributing to the global transition to sustainable energy.

The Norwegian Welfare Model

Norway’s economic model is closely linked to its welfare state, which is one of the most comprehensive in the world. The welfare state is funded primarily through taxes and oil revenues, providing a wide range of services, including healthcare, education, and social security. Social expenditure stood at roughly 22.6% of GDP.

The Norwegian government plays a central role in the economy, with a high level of public ownership and regulation. This model, often referred to as the “Nordic model,” combines a free-market economy with a strong welfare state, ensuring that wealth is distributed more evenly across society. The Norwegian state maintains large ownership positions in key industrial sectors concentrated in natural resources and strategic industries such as the strategic petroleum sector (Equinor), hydroelectric energy production (Statkraft), aluminum production (Norsk Hydro), the largest Norwegian bank (DNB) and telecommunication provider (Telenor).

Figure 11: DNB, the largest Norwegian bank, headquarters.

The government controls around 35% of the total value of publicly listed companies on the Oslo stock exchange, with five of its largest seven listed firms partially owned by the state. When non-listed companies are included the state has an even higher share in ownership (mainly from direct oil license ownership). Norway’s state-owned enterprises comprise 9.6% of all non-agricultural employment, a number that rises to almost 13% when companies with minority state ownership stakes are included, the highest among OECD countries. Both listed and non-listed firms with state ownership stakes are market-driven and operate in a highly liberalized market economy. Government revenues from the petroleum industry are transferred to the Government Pension Fund of Norway Global in a structure that forbids the government from accessing the fund for public spending; only income generated by the funds’ capital can be used for government spending.

The ideological divide between socialist and non-socialist views on public ownership has decreased over time. The Norwegian government has sought to reduce its ownership over companies that require access to private capital markets, and there is an increasing emphasis on government facilitating entrepreneurship rather than controlling (or restricting) capital formation. A residual distrust of the “profit motive” persists, and Norwegian companies are heavily regulated, especially with respect to labor relations.

The welfare state has contributed to Norway’s high standard of living, with low levels of poverty and inequality. Education and healthcare are free at the point of use, and social security provides a safety net for those in need. The government’s focus on social welfare has also supported a high level of social cohesion and trust in public institutions.

Economic Challenges and Future Prospects

- Managing Oil Dependency

One of the biggest challenges facing Norway’s economy is its reliance on oil and gas. While the oil sector has brought significant wealth, it also makes the economy vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices. The transition to a low-carbon economy also presents a challenge, as Norway seeks to balance its role as a major oil producer with its commitment to sustainability.

The emergence of Norway as an oil-exporting country has raised a number of issues for Norwegian economic policy. There has been concern that much of Norway’s human capital investment has been concentrated in petroleum-related industries. Critics have pointed out that Norway’s economic structure is highly dependent on natural resources that do not require skilled labor, making economic growth highly vulnerable to fluctuations in the demand and pricing for these natural resources. The Government Pension Fund of Norway is part of several efforts to hedge against dependence on petroleum revenue.

Figure 12: Norges Bank controls the Norwegian Pension Fund.

The Government Pension Fund Global has been a key tool in managing oil wealth and reducing the economy’s dependence on oil revenues. The fund invests in a diversified portfolio of global assets, providing a buffer against oil price volatility and ensuring that oil wealth benefits future generations.

Norway is also actively working to diversify its economy, with investments in technology, renewable energy, and other sectors seen as key to reducing oil dependency. The government’s focus on education and innovation is aimed at fostering new industries and ensuring that Norway remains competitive in the global economy.

- Demographic Changes

Norway, like many developed countries, faces demographic challenges, including an aging population. The country’s birth rate has been declining, and the proportion of elderly citizens is expected to increase significantly in the coming decades. This trend could put pressure on the welfare state, particularly in terms of healthcare and pensions.

The government has implemented policies to address these challenges, including encouraging higher fertility rates and promoting immigration to boost the workforce. However, managing the economic implications of an aging population will remain a key issue in the coming years.

- Climate Change and Encironmental Sustainability

Climate change is another significant challenge for Norway’s economy. As a country heavily reliant on natural resources, Norway is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including changes in fish stocks, melting glaciers, and increased frequency of extreme weather events.

The Norwegian government has set ambitious targets for reducing carbon emissions and transitioning to a low-carbon economy. This includes investments in renewable energy, carbon capture and storage, and electric transportation.

Norway is also a leader in electric vehicle adoption, with one of the highest per capita rates.

Figure 13: A Tesla in Oslo

Exports/Imports

Main export partners in 2023 were the United Kingdom at 19%, Germany 19%, Netherlands 8.3 %, Sweden 7.7 %, Poland 6.1% and France 5.9 %. Main Import partners were Germany at 11.4 %, China at 11.2%, Sweden at 10.8% , USA at 7.6%, Netherlands at 4.8% and Denmark at 4.7%.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Norway’s economy is a model of effective resource management and social equity. The country has successfully harnessed its natural resources, particularly oil and gas, to build a prosperous and well-functioning welfare state. However, as the world shifts towards sustainability, Norway faces the challenge of reducing its dependence on fossil fuels while maintaining economic stability.

By investing in renewable energy, technology, and other industries, Norway is positioning itself for a future less reliant on oil. With its strong foundation in innovation and a commitment to social welfare, Norway is well-prepared to navigate the economic challenges ahead, continuing its legacy as a resilient and forward-thinking nation.