Introduction

South Africa’s economy holds a paradoxical place in the world. It’s one of the most developed and diversified economies on the African continent. Yet, its potential is persistently undermined by deep structural fragilities.

South Africa is rich in mineral resources. It also has a sophisticated financial system and a strong industrial capacity. These elements have long led to South Africa being viewed as a continental economic anchor.

But beneath the surface, chronic challenges hinder growth. These include crippling power shortages, high inequality and a fragile fiscal position. These issues weigh on investor confidence and limit the country’s ability to deliver broad-based prosperity.

Illustration 1: Flag of South Africa

To understand South Africa’s economic trajectory, one must explore its dual identity. It is a resource-rich, relatively advanced emerging market. However, it struggles to convert its potential into sustained, inclusive growth. The legacy of apartheid, spatial inequality, and state-owned enterprise mismanagement continues to cast a long shadow. Meanwhile, the government is pursuing reform.

Illustration 2: A giraffe spotted during a safari in South African. Image from: How to safari in South Africa on a budget | South Africa holidays | The Guardian

Today, South Africa stands at a crossroads. It could leverage its natural endowments, human capital and reform momentum to enter a new growth phase. Alternatively, it might remain stuck in a low-growth equilibrium, unable to overcome its systemic constraints.

The following article will explore South Africa’s macroeconomic performance, structural strengths, institutional weaknesses and long-term opportunities. We will weave together the latest economic data, reform trends and risk factors. These elements will determine whether South Africa can unlock its promised future.

History and Foundations

Pre-Colonial and Colonial History

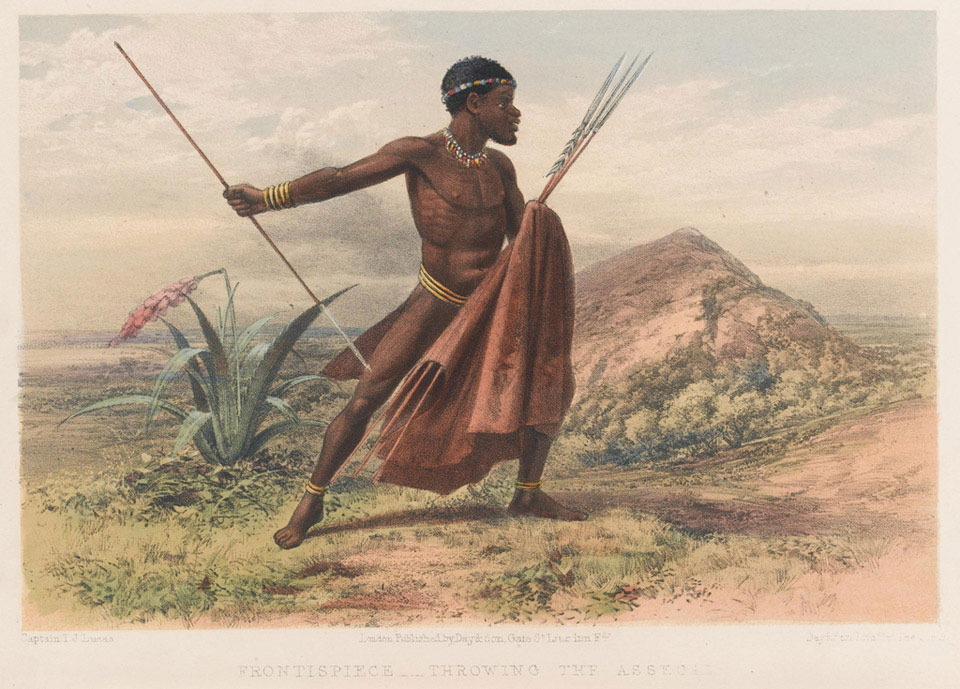

Before European colonization, indigenous communities such as the Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho, and Tswana had well-established systems of agriculture.

They practiced pastoralism and trade. Cattle ownership, artisanal crafts, and local trade networks formed the backbone of their economies. These societies demonstrated significant economic organization and regional exchange, long before colonial influence reshaped the subcontinent.

Illustration 3: “Throwing the Assegai” painting showing a Xhosa warrior from 8th Cape Frontier War (1850-1853). Image from Xhosa warrior, 8th Cape Frontier War, 1850-1853 | Online Collection | National Army Museum, London

European settlers arrived and began a significant change in South Africa’s economy. The Dutch arrived first in 1652. Later, the British followed. Colonization introduced formal property systems, trade oriented toward European markets and the appropriation of land from indigenous populations.

The establishment of the Cape Colony and subsequent British expansion laid the foundation for a dual economy. This favored European settlers. It systematically excluded Black South Africans from wealth creation, land ownership, and political participation.

Discovery of Gold and Diamond

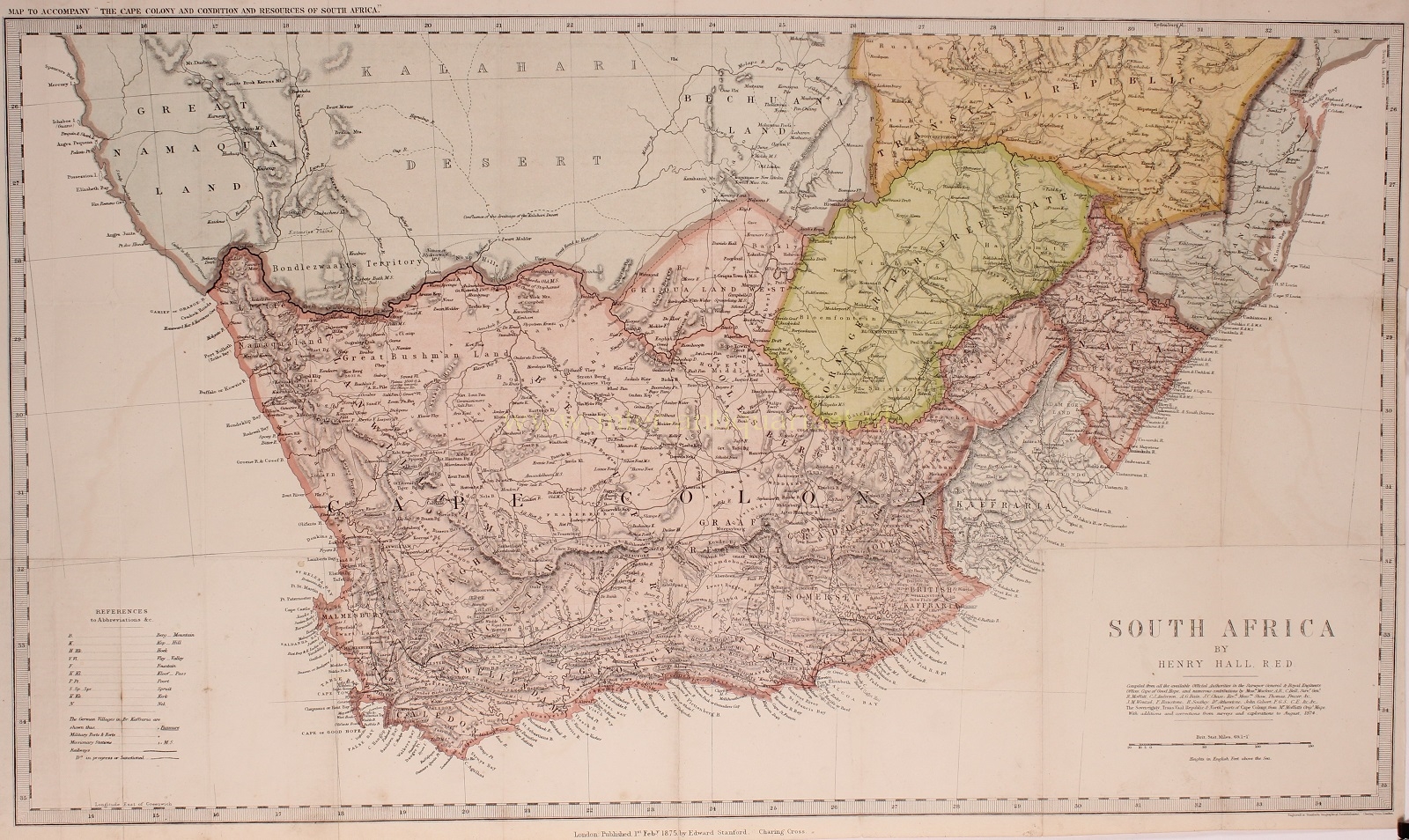

The discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in 1867 began South Africa’s transformation.

Gold was then found in the Witwatersrand in 1886. This discovery turned the nation into a mining powerhouse. These discoveries attracted massive domestic and foreign investment and spurred rapid urbanization.

Mining became the primary driver of the economy, stimulating infrastructure development such as railways, ports and telecommunication networks.

However, it also entrenched social and economic inequalities. The system relied heavily on migrant labor. It drew men from rural areas under harsh conditions to work in mines. Wealth accumulated by mining magnates fueled industrial expansion but remained concentrated within a small elite.

Illustration 4: Image showing Cape Colony in the 19th century.

Industrialisation and Apartheid

Industrialization during the late 19th and early 20th centuries diversified the economy. Manufacturing sectors such as textiles, food processing, and metalwork emerged alongside mining. The formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910 enabled national coordination of infrastructure and economic policy. Protective tariffs encouraged local manufacturing, but mining exports remained central, exposing the economy to global commodity fluctuations.

The formalization of racial segregation, culminating in apartheid after 1948, profoundly shaped the structural foundations of South Africa’s economy.

Illustration 5: A segregation sign in Apartheid South Africa. Image from: Apartheid, Africa’s ‘Jim Crow’ Becomes Law – African American Registry.

The Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 confined Black South Africans to underdeveloped “homelands.” These policies restricted their participation in high-value sectors. Pass laws regulated labor mobility to ensure a steady supply of cheap labor for mines and urban industries. The state supported industrial growth primarily for white-owned businesses.

Black South Africans were largely excluded from ownership. They lacked access to credit and skilled employment. Despite this, industrialization advanced in several areas. Notably, it progressed in energy, transport, and urban manufacturing hubs. This development created a modern industrial base, even within a deeply unequal society.

The late apartheid period brought additional pressures, including international sanctions, divestment, and internal resistance. The economy relied increasingly on mechanized mining, state-owned enterprises and financial markets to maintain growth.

At the same time, rising labor unrest and political instability highlighted structural weaknesses. These inequalities would become central challenges for the post-apartheid era.

The transition to democracy in 1994 marked a turning point. The ANC-led government inherited an economy with advanced infrastructure. It had a strong industrial base and a sophisticated financial sector. However, there was also severe inequality, underdeveloped rural areas, and limited human capital among the majority population.

Early reforms included the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). The Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy also aimed to balance social redress. They pursued macroeconomic stability. They opened South Africa to global trade and foreign investment. These reforms also addressed long-standing inequities.

Modern South Africa

Today, South Africa’s economic structure reflects this layered history. It features a modern, globally integrated industrial and financial sector.

Illustration 6: Boulders Beach in Cape Town, South Africa. Image from: South Africa | National Geographic Kids

The economy of South Africa is currently the largest economy in Africa as of October 2025. It is a mixed economy, emerging market and upper-middle-income economy, and one of only eight such countries in Africa.

Cape Town is SA’s second-largest city by population. It serves as Africa’s tech hub and has a large startup community. The city is popular among digital nomads. The city is home to hundreds of tech firms, and is referred to as the “Startup Capital of Africa”.

Illustration 7: Cape Town, South Africa. Image from: Vacations in South Africa: these are the most beautiful places

However, there are persistent inequalities. A dual labor market exists, along with uneven development between urban and rural areas.

South Africa levies a top personal income tax rate of 45%. It also imposes a corporate tax rate of 27%, alongside value-added and capital gains taxes. This results in an overall tax burden of about 23.4% of domestic income.

Key Industries and Sectors

Mining and Natural Resources

Mining has historically been the backbone of South Africa’s economy, shaping its industrialization, urbanization, and global trade presence. Diamonds were discovered in Kimberley in the late 19th century. This event, followed by the gold rush in the Witwatersrand, established South Africa’s mineral wealth as a global mining powerhouse.

Mining has created employment opportunities, generated export revenue, and funded infrastructure development. Platinum, gold, diamonds, coal, manganese, and chrome remain critical exports. South Africa accounts for a significant share of global supply, especially in platinum and manganese.

Illustration 8: Diamond discovered in Kwazulu-Natal province in South Africa. Image from: South Africa: Thousands rush for “diamonds” in Kwazulu-Natal province | Africanews

In 2019, South Africa ranked among the world’s leading producers of several key minerals. It was the largest global producer of platinum, chromium, and manganese. The country was the second-largest producer of titanium. It was also the third-largest producer of vanadium.

Illustration 9: A mine in South Africa. Image from: World’s deepest gold mine shut down due to COVID-19 | Daily Sabah

The country also held prominent positions in other sectors. It was the 6th-largest producer of iron ore. It ranked as the 11th-largest producer of both gold and cobalt. It was the 15th-largest producer of phosphate. In 2018, South Africa was the world’s 12th-largest uranium producer.

However, the sector faces mounting structural challenges. Ore quality is declining, making extraction more expensive and technologically demanding. Deep-level mining, particularly for gold, involves complex engineering and escalating safety concerns.

Analysts warn that without substantial reinvestment in technology and workforce training, key operations could become economically unviable within decades. Rising operational costs, coupled with fluctuating global commodity prices, place additional pressure on profitability.

Illegal mining, locally referred to as “zama zamas,” presents a parallel challenge. These informal operations not only undermine formal mining companies by diverting resources. They also reduce legal production volumes.

Additionally, they exacerbate safety risks, cause environmental degradation, and complicate regulatory enforcement. Mining companies face significant difficulties navigating bureaucratic delays in permits and licenses. Environmental compliance adds to these issues. These challenges further discourage both domestic and foreign investment.

Environmental and social pressures are also growing. Mining is energy-intensive, water-intensive, and environmentally disruptive, and South Africa faces heightened scrutiny regarding sustainable practices and social responsibility.

Illustration 10: Gold from a Zama Zamas

Communities around mines demand benefits and fair labor practices, while environmental groups emphasize rehabilitation and water management. Transitioning to sustainable mining practices is essential. Adopting modern technology is necessary. Addressing labor and regulatory challenges is crucial if the sector is to remain a pillar of the economy

Mining’s share of South Africa’s GDP has declined from 21% in 1970 to just 6% in 2011. However, the sector continues to dominate the country’s export profile. It accounts for nearly 60% of total exports. Mining also contributes approximately 9% of the nation’s value added.

The industry is anchored by some of the country’s largest and most influential companies. These include Anglo American, one of the world’s leading diversified mining firms. Sibanye Stillwater is a major producer of gold and platinum group metals. Impala Platinum is a top global platinum miner. These companies not only drive significant export revenue but also shape employment, technological innovation, and investment patterns within the sector.

South African Agriculture

Agriculture plays a modest but important role in South Africa’s economy. It formally employs around 5% of the workforce. Additional work is provided through casual and seasonal labor.

Illustration 11: Citrus farming in South Africa. Image from:Citrus farming in South Africa – get in on the excitement! –

The sector contributes approximately 2.8% to national GDP. This is a relatively low share compared to other African countries. However, its social and economic significance extends beyond these figures.

It supports rural livelihoods, food security, and exports. South Africa is a leading exporter of fruit, wine, nuts, and sugar. Its agricultural products, like wine and citrus, reach premium markets globally.

Illustration 12: Vineyard in South Africa near Cape Town. Image from: The Best Wine Regions in South Africa | Jacada Travel.

The sector provides employment in rural areas and is essential for community stability, especially where alternative economic opportunities are scarce.

South Africa is a major global producer of a range of agricultural products. In 2018, the country produced 19.3 million tonnes of sugarcane, ranking 14th worldwide; 12.5 million tonnes of maize, the 12th largest globally; 1.9 million tonnes of grapes and 1.7 million tonnes of oranges, both 11th largest; and 397,000 tonnes of pears, the 7th largest producer in the world.

Beyond these staples, South Africa ranks among the top global producers of several other crops. These include chicory roots and grapefruit (both 4th), cereals (5th), and green maize and maize (7th). Additionally, castor oil seed and pears rank 9th. Sisal and other fiber crops are ranked 10th. Despite its strengths, the sector faces significant challenges, including increasing foreign competition and persistent crime affecting farms.

Farm attacks, in particular, have sparked debate over government intervention. Some critics argue that authorities either over-prioritize this issue or under-prioritize it relative to other forms of violent crime.

Furthermore, agriculture is increasingly vulnerable to climate change, including droughts, shifting rainfall patterns, and water scarcity.

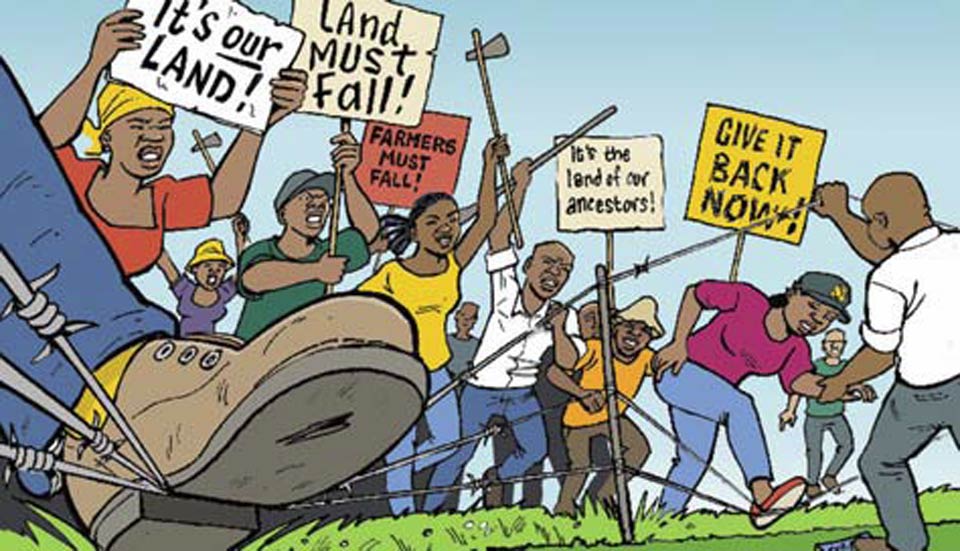

Illustration 13: Land reform continuous to be a very controversial topic in South Africa. Image from: A fresh approach to land reform

Land reform policies, though critical for historical redress, create uncertainty over tenure and investment incentives, slowing modernization and mechanization. Rural infrastructurelm including irrigation systems, transport networks and storage facilities, requires significant development to improve productivity and competitiveness.

Investments in climate-resilient practices, sustainable irrigation, and agro-processing can enhance the sector’s economic impact while addressing social imperatives.

Manufacturing and Industry

South Africa’s industrial sector is diversified. It encompasses downstream mineral processing, automotive manufacturing, and chemicals. It also includes food and beverage processing, machinery, and construction materials.

The manufacturing sector plays a modest role in South Africa’s economy, accounting for approximately 13.3% of employment and contributing around 15% of GDP. Certain segments of the industry are experiencing growth, including advanced sectors such as aerospace and space technology.

While labor costs remain relatively low compared to developed economies, they are higher than in many other emerging markets. At the same time, expenses for transport, communications, and general living add to the overall cost of doing business. These costs present challenges for competitiveness. They also hinder expansion within the sector.

The automotive sector, in particular, is a significant exporter. It employs thousands in assembly plants for both domestic consumption and global markets. The country is also a hub for automotive manufacturing.

It hosts production plants for major global companies. These include BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, Daimler-Chrysler, General Motors, Nissan, and Toyota. Companies producing in South Africa enjoy benefits from relatively low production costs.

Illustration 14: Car Manufacturing hub in South Africa. Image from: Sales of new cars in South Africa on decline – Auto Auto Parts Africa: Connecting African Importers & Buyers

They gain preferential access to new markets through trade agreements with the European Union and the Southern African Development Community. Chemical production, steel and ferroalloy processing, and other industrial activities complement mining, creating an interconnected industrial ecosystem.

Despite these strengths, the sector faces persistent constraints. High electricity costs, largely driven by reliance on Eskom’s aging coal-powered generation fleet and inconsistent supply, create uncertainty for manufacturers.

Power outages and load shedding disrupt production schedules, reduce output, and erode investor confidence. Logistical bottlenecks, including underdeveloped rail systems, port congestion and inadequate road maintenance, further hinder competitiveness, particularly for export-oriented firms.

Illustration 15: South African roads present a challenge for export-driven businesses.

The regulatory environment is intended to protect labor and consumers. However, businesses often cite it as cumbersome and inconsistent. This increases compliance costs and reduces agility. Many manufacturing firms operate at a scale below global competitors.

This limits their ability to achieve economies of scale. It also hinders their capacity to innovate or compete on price. Reforming state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is crucial. Investing in transport infrastructure is also essential. Additionally, reliable energy provision is needed. These actions are widely recognized as prerequisites for revitalizing industrial capacity.

Emerging industrial opportunities exist in high-tech manufacturing, advanced materials and agro-processing. South Africa can leverage its mining expertise in these industries. It can also use its engineering capabilities and research infrastructure. However, realizing this potential requires consistent policy support, streamlined regulation and investment in skills development and technology adoption.

Tourism

Tourism significantly impacts South Africa’s economy. It contributes to both GDP and employment. It also showcases the country’s rich natural, cultural, and historical assets.

Illustration 16: Table Mountain in Cape Town, South Africa. Image from Table Mountain Tour, South Africa | Audley Travel US

South Africa offers a diversity of experiences. The iconic Table Mountain and Cape Town’s vibrant urban culture. The wildlife-rich Kruger National Park. Each destination attracts millions of visitors each year.

.jpg)

Illustration 17: Safari in Kruger National Park, SA. Image from: 3 Day Kruger National Park Safari – Kruger Lodge Tour

The scenic Drakensberg mountains further enhance its appeal. The tourism industry supports a wide range of jobs. This includes hospitality, travel services, transportation, and cultural attractions. These are particularly important in regions where other employment opportunities are limited.

South Africa is renowned for wine tourism. It is also famous for its culinary attractions. The Cape Winelands region is a major draw for international visitors. However, the sector faces several challenges. These include seasonal fluctuations, infrastructure bottlenecks, and concerns over safety and security. These challenges can influence traveler perceptions.

Exchange rate volatility affects inbound tourism. Global economic trends also play a role. They make the industry highly sensitive to both domestic and international developments.

Despite these challenges, tourism remains a strategic sector for foreign exchange earnings. It contributes to regional development and promotes South Africa’s global brand.

Finance

South Africa’s financial sector is highly sophisticated on the African continent. It boasts a well-developed banking system, capital markets, and insurance sector. M

ajor banks such as Standard Bank, FirstRand, and Absa provide a broad range of services. International institutions operating locally also offer retail, corporate, and investment services.

The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) is the largest in Africa. It serves as a key hub for capital raising, equity trading, and investment. It connects South African companies with domestic and international investors.

Illustration 18: The city of Johannesburg, South Africa which is major African finance hub. Image from Moving to South Africa – Living in Johannesburg.

The insurance sector includes firms such as Old Mutual and Sanlam. It plays an important role in risk management. It also contributes to wealth preservation.

The financial sector is highly advanced. However, it faces challenges related to regulatory compliance, cyber-security risks, and ensuring financial inclusion for underserved populations.

Efforts to expand access to banking, mobile finance, and fintech solutions are ongoing. These efforts aim to integrate a broader segment of the population into the formal financial system. The robustness of the financial sector positions South Africa as a regional financial hub.

Informal Economy

The informal economy is a critical part of South Africa’s socioeconomic landscape. It provides employment and income for millions. These individuals are unable to access formal labor markets.

Illustration 19: A township in Cape Town, South Africa witht the table mountains in the background. Image from: Error 404 : Not found | My Guide Cape Town

Activities in this sector include street vending, small-scale trade, domestic work, informal transport services, and artisanal production. The informal economy is particularly vital in urban townships and rural areas. It helps sustain livelihoods and supports local communities.

Despite its importance, the sector faces significant challenges. Workers often lack legal protections, access to credit, and social security. They also lack regulatory recognition. This makes them vulnerable to economic shocks. C

rime, market restrictions, and limited infrastructure further constrain informal businesses. The informal economy contributes significantly to household income and local economic activity. It acts as a buffer against unemployment and poverty. This highlights its social and economic importance alongside formal sectors.

Green Energy and Transition

South Africa’s transition to a green economy represents both a challenge and a significant opportunity. The country is rich in critical minerals essential for renewable energy technologies. These include lithium, cobalt, nickel, and platinum group metals.

This positions it to benefit from the global shift toward electric vehicles and battery storage. Strategic investment in these minerals, combined with sustainable mining practices, could create high-value export opportunities and stimulate industrial innovation.

Scaling renewable energy production is central to this transition. Solar, wind, and hydroelectric projects can reduce reliance on coal, mitigate environmental impact, and stabilize energy supply.

Expanding the transmission grid, encouraging private investment, and reforming energy governance are vital to unlocking the green economy’s potential.

According to the OECD, integrating renewable energy could support emissions reduction targets. Electrification of transport and clean-energy industrialization can also create new jobs. These strategies diversify the economy and enhance global competitiveness.

Illustration 20: Solar panels being installed in South Africa.

However, success depends on coordinated policy, regulatory clarity, and investment in human capital. South Africa must address governance bottlenecks.

It also needs to tackle infrastructure gaps and financing challenges. Otherwise, it risks underutilizing its renewable potential. Additionally, South Africa may miss opportunities in the rapidly growing global green economy.

Fiscal Health and Macroeconomics

South Africa’s macroeconomic trajectory has been sluggish in recent years. According to the IMF, growth was only 0.7% in 2023, constrained by persistent power outages and logistical bottlenecks in rail and port operations.

The OECD likewise estimates that economic activity slowed to around 0.6% in 2024, reflecting continued uncertainty and infrastructure bottlenecks.

This weak growth has major implications for fiscal health. Public debt has ballooned: from 31.5% of GDP in 2010 to a projected 77% by 2025, according to OECD data.

The cost of servicing this debt is rising sharply. The OECD estimates that by 2025, interest payments will absorb roughly 5.2% of GDP, a major drain on the state’s ability to fund other priorities. These fiscal pressures limit the government’s capacity to invest in infrastructure. They also hinder investment in education and social programs. These elements are the very levers needed to unlock long-term growth.

At the same time, the IMF notes that inflation has moderated: from around 5.9% in 2023 to an estimated 4.5% in 2024, and the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) responded by cutting interest rates. This easing of monetary policy provides some breathing room, but it is balanced against the risk of weakening fiscal discipline.

Illustration 21: Traditional South African Instruments. Image from: South Africa Culture and Traditions: What to know | Goway Travel

Comparison with other emerging markets

South Africa stands out among emerging markets in several areas. Its financial markets are among the most developed on the continent. They offer relatively easy access to capital. The country has competitive business tax rates compared with peers.

Transport infrastructure includes ports, rail networks, and roads. It is generally considered superior to that of many emerging economies, such as India, Brazil, Mexico, and China. However, it still lags behind advanced emerging markets like South Korea and Chile.

Illustration 22: A black rhino in the marataba private reserve. Image from: Conservation and the Big Five on a South Africa Safari.

Foreign direct investment has historically been strong, at over 3% of GDP in the late 2000s, reflecting international confidence in certain sectors of the economy.

Despite these strengths, South Africa faces structural challenges that hinder its competitiveness relative to other emerging economies. Labour costs are higher than in most peer countries, and the availability of skilled workers is constrained by an underperforming education system.

The country’s domestic market is relatively small, limiting scale advantages that nations like China and India enjoy. Moreover, energy supply has been unreliable, with frequent power shortages affecting industrial output and investor confidence.

Illustration 23: University of Stellenbosch, one of the highest ranked South African Universities. Image from: SAHRC finds Stellenbosch University violated human rights of Afrikaans-speaking students with English-only policy – SA People.

Innovation and technology adoption are also slower compared with leading emerging markets. This makes it difficult for South Africa to maintain a high-growth trajectory in advanced manufacturing or tech-driven sectors.

On a more positive note, the country has niche strengths, like in aerospace and space technology. South Africa joined the BRICS group in 2011. This inclusion cemented its position among major emerging economies. It provided increased global visibility and created opportunities for investment.

However, to sustain competitiveness, the country needs to improve education. It must invest in infrastructure and ensure a stable energy supply. Policies should be implemented to enhance innovation and productivity. These measures will ensure the country does not fall behind rapidly developing peers.

Inequality and Social Dynamics

One of the most destabilizing aspects of South Africa’s economic challenge is unemployment, particularly chronic and youth unemployment. The OECD reports that the formal employment rate remains low. Only a relatively small share of the working-age population participates in productive, high-quality jobs.

According to IMF data, the unemployment rate was estimated at 32.8% in 2024. Many young people, especially in marginalized communities, find themselves locked out of labor‑market opportunities. This weak job creation is not just a social issue, it undermines human capital development and limits consumer demand.

Inequality in South Africa is profound and persistent. The World Bank notes a very high Gini coefficient for income. Additionally, a significant portion of the population lives in poverty.

Illustration 24: Protests against the high unemployment rate in South Africa . Image from South Africa’s unemployment rate rises to 32.9% | Lagos to Jozi Blog

Social grants help to cushion the poorest, but they are not a substitute for meaningful inclusion in economic activity. According to OECD analysis, many of the unemployed rely on social assistance.

The spatial legacy of apartheid remains evident. Many low-income households live far from economic hubs. This distance exacerbates inequalities. It makes labor mobility and access to opportunity difficult.

Illustration 25: Two different neighborhoods in South Africa illustrating the inequality.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) also contribute to social strain. Governance failures, corruption, and inefficiency within SOEs drain public resources.

Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) is a policy framework in South Africa designed to redress the economic inequalities created by apartheid. However, the program has faced criticism for benefiting a relatively small elite. It has not broadly

In 2002, roughly 62% of black Africans lived below the poverty line. About 29% of coloured and 11% of Indians were also below the poverty line. Additionally, 4% of whites lived below the poverty line. Average incomes have risen unevenly. Black households increased from R6,018 in 1993 to R9,718 in 2008. In contrast, white households rose from R29,372 to R110,195.

Median income grew much less than the mean, showing that wealth gains are concentrated among the richest. The black middle class and wealthy population have expanded despite these challenges. Nearly 40% of the richest 10% are now black.

Land Reform and Land Distribution

Land reform has been a central and highly sensitive issue in South Africa since the end of apartheid. The legacy of racially skewed land ownership continues to shape the country’s social and economic landscape.

Under colonial and apartheid rule, a white minority owned most productive land. In contrast, the black majority was confined to underdeveloped homelands or smallholdings.

Illustration 26: Villa near Cape Town, South Africa. Image from: The 20 Best Luxury Villas near Cape Town in 2024

The government’s land reform program seeks to address these historical injustices. It does so through three main pillars: land restitution, land redistribution, and tenure reform.

Land restitution provides compensation or returns land to those dispossessed under discriminatory laws. Land redistribution aims to transfer land to historically disadvantaged individuals. Tenure reform secures rights for people living on communal or leased land.

Despite these efforts, progress has been slow and uneven. By 2020, only about 10% of agricultural land had been redistributed. Many beneficiaries struggle with limited access to finance, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of farming experience, which in some cases has led to reduced productivity.

The debate over expropriation without compensation (EWC) has intensified in recent years.

Proponents argue it is essential to accelerate equity. They believe it will empower rural communities. Critics warn that poorly implemented EWC could threaten agricultural output. It might also deter investment and harm food security.

Trade and Global Position

South Africa’s economy is closely tied to global markets, with exports accounting for roughly 30% of GDP.

Minerals dominate its export profile, including platinum, gold, diamonds and iron ore, while automotive manufacturing, agriculture and chemicals also contribute significantly.

Imports are concentrated in machinery, electronics, petroleum, and chemicals. This creates structural dependencies. These dependencies make the economy sensitive to global price fluctuations.

China, the European Union, the United States, and neighboring African countries are South Africa’s main trading partners. China receives a large share of metals and minerals. Germany imports vehicles and machinery.

Regional trade through the SADC supports food and manufactured goods exports. Trade agreements with the EU, AfCFTA, and other partners provide market access and encourage foreign investment.

Illustration 27: Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sergei Lavrov meets with South African Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor during a press conference in Pretoria, South Africa, on Jan. 23. Image from: Ukraine-Russia War: Fallout From South Africa’s Alleged Arms Shipments to Russia

The South African rand (ZAR) plays a critical role in trade but is highly volatile. The South African Reserve Bank manages inflation and currency fluctuations through monetary policy, but global capital flows often influence outcomes.

Illustration 28: Two Hundred Rand. Image from Rand | Exchange Rate, Inflation & Devaluation | Britannica Money.

Exports remain heavily commodity-based. Metals and minerals contribute around 60% of export revenue. Agriculture accounts for about 10%, and manufactured goods roughly 20%.

Imports are dominated by machinery, electronics, and petroleum. Export-oriented manufacturing hubs and industrial incentives aim to diversify trade. However, reliance on raw materials exposes South Africa to commodity price swings. It also makes South Africa vulnerable to global economic cycles.

Credit Rating

South Africa’s sovereign credit rating is a key indicator of its fiscal stability and investment risk. Moody’s currently assigns the country a Baa3 rating with a negative outlook.

This highlights the pressures from high public debt. The country also faces persistent budget deficits and ongoing support requirements for state-owned enterprises such as Eskom.

Fitch and Standard & Poor’s both rate South Africa at BB+ with negative outlooks. They emphasize structural challenges. These include slow economic growth, high unemployment, inequality, and policy uncertainty.

Historically, South Africa maintained investment-grade ratings in the early 2000s, supported by strong institutions and fiscal discipline. However, repeated downgrades over the past decade show the impact of rising debt, energy constraints, and slow reforms. These issues have increased borrowing costs and affected investor confidence.

The negative outlook indicates that further fiscal deterioration could lead to additional downgrades. Policy missteps might also trigger such downgrades.

On the other hand, successful reforms could stabilize the country’s ratings. Improved economic performance could even enhance the ratings.

Illustration 29: a springbok, image from Wildlife in South Africa – Types of South African Animals – A-Z Animals

Risk and Vulnerabilities

The risks facing South Africa’s economic future are both immediate and structural. The energy crisis remains the single largest drag. Load shedding eased in 2024, but the system remains fragile. Outages returned in early 2025.

Many firms, especially SMEs still lack the capital to build their own backup power, making them especially vulnerable. SOEs remain a fiscal risk.

Illustration 30: Eskom coal plant near Johannesburg. Image from: Eskom, Esko, Esk … load shedding – Salaamedia

Entities like Eskom and Transnet need deep governance reform, capital injection, and operational restructuring. If mismanagement continues, these companies could remain a drag on government finances. They might fail to deliver the infrastructure needed for growth

South Africa faces a persistent and severe employment problem, with unemployment rates among the highest in the world. As of 2025, the official unemployment rate hovers around 33%, while youth unemployment exceeds 60%.

Informal employment remains widespread, providing livelihoods but often lacking stability, social protections or career advancement. High unemployment exacerbates inequality and fuels social tensions. It also constrains domestic demand. Therefore, job creation is a central challenge for sustainable economic growth.

South Africa experiences significant human capital flight. Many skilled professionals leave for countries offering better pay, safety, and career opportunities.

This “brain drain” is caused by high crime rates. It is also due to political instability, slow economic growth, and limited prospects in the domestic labor market.

The loss of talent hampers productivity. It reduces innovation and weakens critical sectors. This situation makes it a persistent challenge for the country’s long-term economic development.

Illustration 31: South Africa is experiencing significant brain drain. Image from: Immigration and “Brain Drain” – Econlib

Corruption and weak institutional capacity also pose major risks. Without credible institutions, investor confidence will remain fragile, and reform momentum could stall.

The country has a very high ratio of social benefit recipients to taxpayers. Since 1994, social spending has been heavily directed toward black households. Today, black South Africans receive roughly 80% of government transfers while contributing around half of total taxes.

The transition to a greener global economy presents both opportunities and risks. If South Africa fails to modernize its mining sector, it could be left behind. This is especially true as demand for green metals surges.

Strengths and Long-Term Opportunities

South Africa’s economy stands out for its strong and diverse foundations. It is one of the most diversified economies on the African continent. The country has well-developed sectors in mining, manufacturing, finance, agriculture, tourism, and services.

The country has an abundance of natural resources. These include gold, platinum, diamonds, coal, and other rare minerals. This wealth continues to be a major economic driver.

It is also a key attraction for global investors. This rich resource base has also helped build a sophisticated mining industry with world-class expertise.

Another major strength is South Africa’s advanced financial sector. Johannesburg hosts one of the largest and most developed stock exchanges in the world. Stable banking institutions and sound regulatory frameworks support it.

The country also benefits from strong physical infrastructure. It includes an extensive network of highways, rail systems, and modern ports. These facilitate efficient trade and logistics. Its energy and telecommunications infrastructure are among the best in the region.

South Africa’s workforce is comparatively skilled. This is particularly true in technical, engineering, and financial fields. This expertise supports the country’s industrial and service sectors.

The nation serves as a strategic gateway. It provides a strong base for companies seeking access to the rest of Africa and their regional operations. The growing technology, renewable energy, and automotive sectors further enhance South Africa’s long-term economic potential.

Illustration 32: The economy of South Africa can have a bright future given its resource rich environment and skilled workforce. Image from The future of South Africa: seven things that need to happen | ISS Africa.

Leave a Reply