Introduction

Toyota Motor Corporation is a globally renowned Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer, widely regarded as one of the world’s leading innovators in mobility, automotive engineering, and sustainable transportation.

Illustration 1: he Toyota logo, a symbol of trust, innovation, and global mobility.

Headquartered in Toyota City, Japan, the company is best known for its high-quality vehicles and pioneering work in hybrid technology, but its operations span a broad spectrum including robotics, AI, autonomous driving, and hydrogen fuel cell systems.

Unlike many Western automakers that evolved in tandem with the American and European car industries, Toyota carved a unique path grounded in the principles of Kaizen (continuous improvement) and Just-In-Time manufacturing, revolutionizing global automotive production with the Toyota Production System (TPS). Its reputation for reliability, efficiency, and innovation has made it a household name in markets around the world.

Toyota is consistently ranked among the top global automakers by volume and market capitalization. It has spearheaded the automotive industry’s shift toward sustainability through its leadership in hybrid technology (beginning with the Prius) and its bold push into hydrogen-powered and battery electric vehicles. With a growing focus on AI, connected vehicles, and mobility-as-a-service, Toyota continues to shape the future of transportation.

History

Toyota was founded in 1937 by Kiichiro Toyoda, evolving from Toyoda Automatic Loom Works. Initially focused on producing passenger cars for the Japanese market, the company quickly established itself with models like the Toyota AA and developed a reputation for durable vehicles in the post-war period.

Illustration 2: The first Toyota passenger car was the Toyoda Model AA

The real global breakthrough came during the 1970s and 1980s, when Toyota expanded aggressively into North America and Europe. Its compact, fuel-efficient cars, such as the Corolla and Camry, gained popularity during the oil crisis, helping it gain a foothold in key international markets.

Toyota became a global icon of manufacturing excellence with the development of the Toyota Production System (TPS) which is a manufacturing philosophy that transformed supply chains worldwide. In 1997, it launched the Prius, the world’s first mass-produced hybrid electric vehicle, cementing Toyota’s role as an environmental pioneer in the auto industry.

In the 2010s, Toyota expanded into next-generation mobility, investing in AI research, autonomous driving (under its subsidiary Woven by Toyota), and alternative energy sources such as hydrogen fuel cells (Mirai). The company has continued to build its brand as not just an automaker but a mobility solutions provider.

Today, Toyota operates over 50 manufacturing facilities worldwide and sells vehicles in more than 170 countries. It remains the world’s largest automaker by units sold, combining innovation with a deep commitment to quality and sustainability. Its reputation is that their cars will last for ever due to their quality.

Operations and Production

- Portfolio

Toyota is a car company and it’s core operations center around the development, manufacturing, and sale of automobiles, including sedans, SUVs, trucks, and commercial vehicles. Its flagship models include the Corolla (the world’s best-selling car), Camry, Land Cruiser, Hilux, RAV4 and Prius hybrid.

Illustration 3: Toyota Land Cruiser is one of the most famous Toyota cars

The Toyota Motor Corporation owns several key brands:

- Toyota (mainstream brand)

- Lexus (luxury vehicles)

- Daihatsu (compact cars and mini-vehicles)

- Hino (commercial trucks and buses)

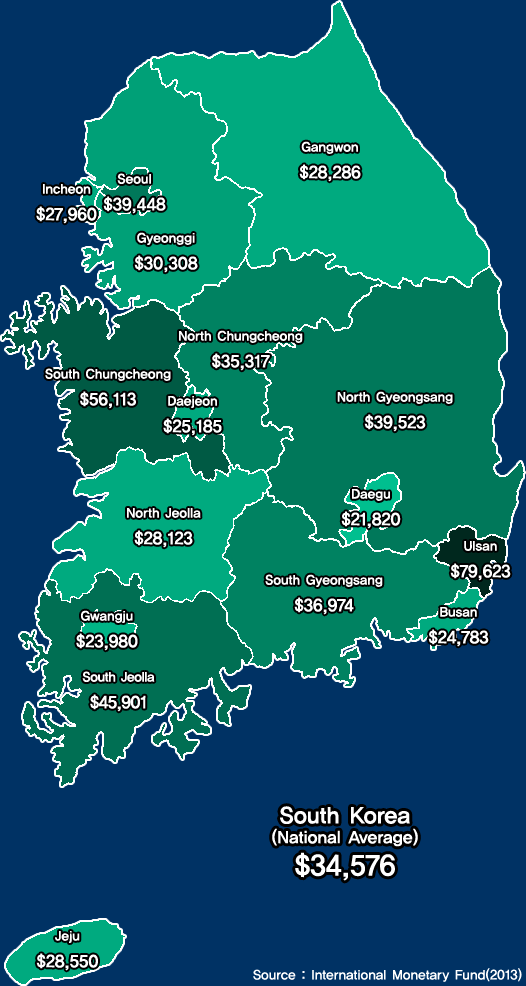

Toyota sells cars in all countries, but its biggest markets are asia and Japan.

Illustration 4: Illustration of the biggest markets of Toyota

- Electric and Hybrid Cars

Toyota has been a pioneer in hybrid technology since the launch of the Prius in 1997, the world’s first mass-produced hybrid electric vehicle. This bold move not only positioned Toyota as a technological leader but also sparked a global movement toward cleaner and more fuel-efficient vehicles. As of today, Toyota has sold over 20 million hybrid vehicles worldwide, contributing significantly to global CO₂ emissions reduction in the transportation sector.

Toyota’s hybrid portfolio is among the most comprehensive in the industry, spanning sedans, SUVs, and even commercial vehicles. Models like the RAV4 Hybrid, Corolla Hybrid, and Camry Hybrid continue to perform strongly in markets across Asia, North America, and Europe. Toyota is known for it’s longevity, quality and sustainability and it has proved that it can produce hybrid cars that are as solid as its gasoline cars.

Illustration 5: Prototype of a new Toyota car that is to come out by 2026

In addition to hybrids, Toyota is expanding its presence in battery electric vehicles (BEVs). Under its new “bZ” (beyond zero) sub-brand, Toyota has launched the bZ4X, a fully electric crossover SUV, and plans to introduce over 10 new BEV models by 2026.

Toyota also produces hydrogen-powered cars as it intorduced Toyota Mirai, one of the few hydrogen-powered cars available to the public, in 2014. Toyota is also investing heavily in solid-state battery research. These next-generation batteries promise higher energy density, faster charging times and greater thermal stability, which could solve many of the limitations of current lithium-ion technology. Toyota aims to begin commercial production of solid-state batteries as early as 2027–2028, potentially reshaping the EV landscape.

- Autonomous Driving, Robotics and AI

Under its innovation hub Woven by Toyota, the company is developing technologies for autonomous vehicles, smart cities, and connected mobility. Toyota’s Guardian system enhances driver safety through AI-driven assistive features, while its Chauffeur system aims for full autonomy in the future.

Toyota is also building Woven City, a fully connected smart city near Mt. Fuji to test smart infrastructure, robotics, and autonomous vehicles in real-life settings.

Beyond cars, Toyota is developing robotics for elderly care, manufacturing automation, and personal assistance. It has also invested in AI research, including partnerships with Stanford and MIT, and launched the Toyota Research Institute (TRI) to explore machine learning, robotics, and materials science.

Key Competitors

Toyota operates in one of the most competitive and rapidly evolving industries, facing rivals across traditional automaking, electric mobility, autonomous driving, and smart mobility ecosystems. Its competitors can be grouped into three main categories:

1. Traditional Global Automakers

- Volkswagen Group: Toyota’s closest global rival by sales volume. Volkswagen has committed heavily to electrification, launching the ID. series of EVs and investing over €180 billion in digital and sustainable technologies. Its scale and global manufacturing footprint mirror Toyota’s, making the two firms frequent contenders in both developed and emerging markets.

- General Motors (GM): Strong in North America and China, GM is transitioning aggressively to EVs under its Ultium battery platform and brands like Chevrolet, GMC, and Cadillac. GM’s Cruise division is also a key player in autonomous mobility.

- Ford Motor Company: Ford competes in global markets, particularly in trucks, SUVs, and commercial vehicles. Its F-150 Lightning electric pickup and investment in self-driving (via Argo AI, now winding down) reflect its growing focus on innovation.

- Honda: Fellow Japanese automaker and frequent rival in efficiency, reliability, and innovation.

2. Electrification and Mobility Disruptors

- Tesla: As the world’s leading electric vehicle manufacturer, Tesla has redefined customer expectations in EV range, software, and direct-to-consumer sales. While Toyota is far ahead in hybrids and hydrogen, Tesla currently leads in BEV market share and autonomous software development.

- BYD: China’s largest EV maker, BYD has quickly become a dominant force in battery-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles. With vertical integration of battery and semiconductor manufacturing, BYD poses a strong challenge to Toyota’s market position in Asia and Latin America.

- Hyundai-Kia: Rapidly growing with vehicles like the Ioniq 5 and EV6, the Hyundai Motor Group also invests heavily in hydrogen fuel cells, autonomous driving (via Motional), and design innovation. Hyundai’s ambition and product breadth increasingly rival Toyota’s.

Illustration 6: A Toyota dealership

3. Tech Giants and AI Innovators

- Apple and Google (Alphabet): Though not automakers per se, both companies are developing autonomous driving software and in-vehicle infotainment platforms. Google’s Waymo and Apple’s rumored “Apple Car” project symbolize the convergence of automotive and digital ecosystems.

- NIO, XPeng, and Li Auto: Chinese EV startups are innovating rapidly in autonomous driving, digital UX, and direct sales models, supported by China’s strong EV policies.

Competitive Advantage

Toyota’s most defining advantage lies in its lean manufacturing and Kaizen culture. This system allows Toyota to produce high-quality vehicles with minimal waste and exceptional efficiency—offering a competitive edge in both cost control and scalability.

Its early leadership in hybrid technology has given Toyota unmatched experience in powertrain integration and fuel efficiency. Toyota’s scale, supply chain mastery, and reputation for reliability allow it to produce high-quality vehicles at competitive prices.

Rather than focusing solely on battery electric vehicles, Toyota has embraced a diverse electrification roadmap: hybrids, plug-in hybrids, BEVs, and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. This approach gives Toyota flexibility across different markets and infrastructures, particularly in countries where charging infrastructure is underdeveloped.

Toyota is consistently ranked among the top brands for quality, safety, and long-term dependability. Its vehicles often command premium resale value and customer loyalty, helping sustain market share in competitive regions. Toyota invests heavily in R&D (over ¥1.2 trillion annually), with a focus on AI, robotics, connected mobility, and next-generation batteries. Its internal ventures like the Toyota Research Institute (TRI) and Woven by Toyota exemplify its commitment to transforming from a carmaker into a mobility technology company

Illustration 7: Toyota Prius is a pioneer when it comes to hybrid cars

Future Outlook

Toyota is at a pivotal moment as the global auto industry transitions to electrification, autonomy and digital mobility. The company aims to sell 3.5 million battery electric vehicles annually by 2030, alongside continued leadership in hybrids and hydrogen.

Its investments in solid-state batteries, next-gen EV platforms and smart cities indicate a long-term strategy rooted in technological leadership and environmental responsibility.

As governments tighten emissions regulations and consumers demand cleaner, smarter mobility solutions, Toyota’s hybrid legacy, global reach, and evolving tech ecosystem position it as a mobility leader for the 21st century.

Stock Analaysis

In this section we will analyze Toyota’s stock to see if it is a good stock to buy or not. Our philosophy is value investing meaning that we try to find good quality companies that are undervalued. However, we will give a holistic overview so all kind of investors with different philosophies can judge the stock for themselves.

Revenue and Profits

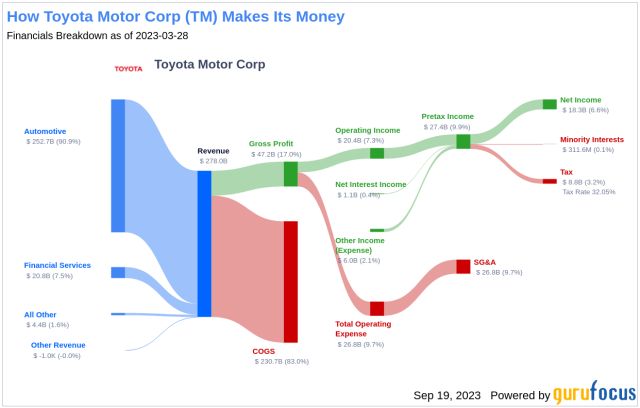

Illustration 8 and 9: Revenue of Toyota Motor Corporation from 2009 to 2025

As shown in Illustrations 6 and 7, Toyota has maintained steady and consistent revenue growth from around USD 209 billion in 2009 to around 317 billion in 2025, without major spikes or declines. This smooth upward trajectory is a strong green flag, reflecting Toyota’s disciplined operations, global market balance, and long-term strategy.

Even through global disruptions like COVID-19 and supply chain challenges, Toyota’s lean manufacturing and diversified product mix helped it maintain growth. Its cautious but forward-looking investments in hybrids, EVs, hydrogen, and smart mobility have supported revenue expansion without volatility.

Overall, Toyota’s financial performance is a green flag for value investors as it shows a company that is stable, has increased its revenue steadily over time and been able to grow and handle crisis.

Illustration 10 and 11: Net Income of Toyota Motor Corporation from 2009 to 2025

Net income is a crucial metric to evaluate when determining whether a company is a worthwhile investment. It represents a company’s net profit or loss after accounting for all revenues, income items, and expenses, calculated as Net Income = Revenue – Expenses.

As seen in Illustrations 10 and 11, Toyota’s net income has followed a stable and upward trend from 2009 to 2025, closely mirroring its consistent revenue growth. Unlike many global automakers or tech firms, Toyota has avoided major profit volatility, thanks to its efficient cost structure, strong global demand, and disciplined investment strategy. This alignment between revenue and net income is a strong green flag, reflecting Toyota’s ability to innovate while maintaining healthy margins and financial stability.

Revenue Breakdown

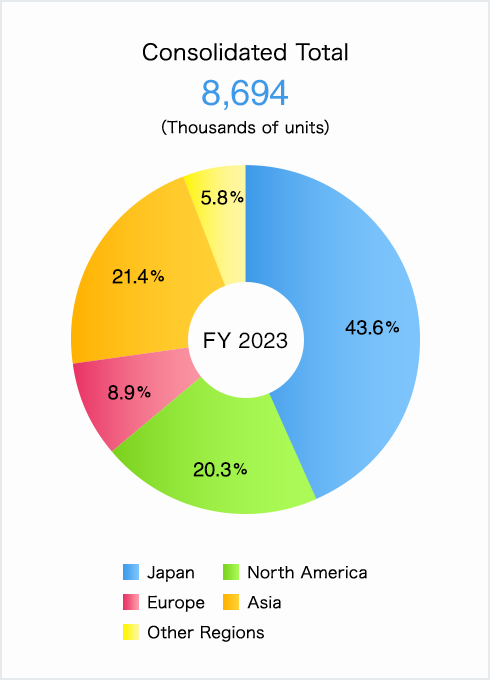

Illustration 12: Revenue breakdown for Toyota Motor Corp. made by guru focus

As shown in Illustration 12, Toyota’s core automotive operations remain its largest revenue driver, consistently contributing over 90% of total revenue. This includes sales of passenger vehicles, commercial trucks, and parts across global markets. Toyota’s diverse portfolio, from the Toyota Corolla and RAV4 to Lexus luxury models and Hilux pickups, provides broad appeal across customer segments and regions. Its leadership in hybrid technology has been a key factor in sustaining strong vehicle demand and repeat sales.

In addition to vehicle sales, Toyota’s financial services segment, offering leasing, loans, and insurance, accounts for approximately 7.5% of total revenue. This arm supports the company’s retail strategy by providing in-house financing for customers and dealers in major markets like the U.S., Europe, and Japan. It also generates stable recurring income, even during periods of lower vehicle sales.

Emerging technologies and mobility initiatives, including hydrogen fuel cell systems, battery electric vehicles (BEVs), autonomous driving (via Woven by Toyota), and AI-powered mobility platforms, contribute a small but growing portion of revenue, currently estimated at 1.6%. While not yet significant in financial terms, these areas are central to Toyota’s long-term transformation strategy and have seen growing R&D allocation.

Toyota’s heavy investment in R&D, consistently around 8–9% of revenue, supports innovation in electrification, AI, robotics, and autonomous driving. While these initiatives contribute to short-term cost pressure, they are considered essential for maintaining technological leadership and complying with future regulatory standards.

In terms of profitability, Toyota maintains strong gross margins across its core business due to operational efficiency, economies of scale, and its renowned Toyota Production System (TPS). However, newer segments like BEVs and hydrogen mobility currently have higher development and production costs, which modestly impact overall margins as they scale.

Overall, Toyota’s revenue structure reflects both stability and forward-looking diversification. Its core business provides predictable cash flow, while its investments in next-generation mobility position the company for leadership in a rapidly evolving automotive landscape.

Earnings per Share

Illustration 13: Earnings per share for Toyota Motor Corp. from 2009 to 2025

Earnings Per Share (EPS) is a key financial metric that measures a company’s profitability on a per-share basis. It indicates how much profit a company generates for each outstanding share of its stock, and is used to assess a company’s financial health, profitability, and potential for growth. In other words this metric can tell us how profitable the business is.

The EPS figure itself isn’t the primary focus for value investors, it can be 0.2 or 10, but what truly matters is the company’s ability to generate consistent earnings growth. A steadily increasing EPS over time signals strong financial health, profitability, and long-term value creation.

Toyota’s earnings per share from 2009 to 2025 shows an increase over time from -2.88 in 2009 to 23.73 in 2025. This reflects a remarkable turnaround and long-term financial strength, driven by consistent global demand, operational efficiency through the Toyota Production System, and strategic investments in hybrid and next-generation mobility technologies. The steady growth in EPS highlights Toyota’s ability to generate sustainable profits even amid industry disruptions, regulatory changes, and rising R&D spending, positioning it as one of the most resilient and reliable companies in the global automotive sector and is a green flag for investors.

Assets and Liabilities

Illustration 14 and 15: Assets and Liabilities for Toyota from 2009 to 2025

When evaluating a company as a potential investment, understanding its assets and liabilities is crucial. If a local business owner offered to sell their shop to you, one of the first questions. after determining its profitability, would be about its equity and assets. The same principle applies when assessing publicly traded companies like Toyota.

As shown in Illustrations 14 and 15, Toyota has built a substantial asset base, totaling approximately $621 billion in 2024. This steady asset growth from 2009 to 2024 is a strong positive indicator, reflecting the company’s ongoing expansion, long-term investments in electrification, autonomous technology, and manufacturing infrastructure.

At the same time, Toyota’s total liabilities have also increased over the years, rising from approximately $193 billion in 2009 to over $378 billion in 2024. While this rise in liabilities may raise concerns for some investors, it is not necessarily a red flag, as much of it is tied to Toyota’s financial services arm and ongoing investments in electrification, autonomous driving, and next-generation mobility infrastructure. These capital-intensive areas are critical for maintaining Toyota’s global competitiveness and future readiness. Historically, Toyota has maintained a strong balance between investment and financial discipline, supported by robust cash flows and consistent profitability. Nevertheless, the scale of its liabilities warrants continued observation. Investors should monitor Toyota’s ability to manage debt responsibly, ensuring that it does not limit strategic flexibility or affect long-term financial stability as the automotive industry continues to evolve.

The key factor for investors is whether Toyota can effectively manage its debt while maintaining strong revenue and profitability. If the company can generate consistent cash flow and sustain high demand for its products and services, its rising liabilities may not be a major issue. However, if debt levels continue to grow faster than revenue or profits, it could indicate financial strain, making it important for investors to monitor the company’s ability to service its obligations while maintaining profitability.

Toyota’s cash on hand in 2024 is notably less than its long-term debt, which raises some concerns about its liquidity position. Holding less readily available cash compared to its debt obligations may indicate potential challenges in meeting short-term financial commitments without relying on additional financing or asset sales. This imbalance could limit Toyota’s flexibility to fund strategic investments or navigate unexpected market downturns, and investors should monitor the company’s cash flow management closely to assess any risks related to its financial stability. This should be monitored closely by all investors.

As seen in Illustration 15, Total Shareholder Equity, calculated as total assets minus total liabilities, has consistently grown over the past 14 years. This is a positive indicator for potential investors, as it suggests that Toyota is building value over time rather than eroding its financial foundation. A steadily increasing shareholder equity indicates that the company’s assets are growing at a faster rate than its liabilities, which is a green flag for financial health. This trend suggests that Toyota is successfully expanding its operations while maintaining a solid balance sheet. Additionally, rising equity provides a buffer against financial downturns, making the company more resilient in times of economic uncertainty. However, investors should also consider how this growth is achieved, whether through profitable operations or increased debt financing, to fully assess the sustainability of this trend.

Debt to Equity Ratio

Illustration 16 and 17: Debt to Equity ratio for Toyota Motor Corp. from 2009 to 2024

The Debt-to-Equity (D/E) ratio is an important financial metric for assessing a company’s financial leverage and risk. It compares the amount of debt the company uses to finance its operations relative to its shareholder equity. A high D/E ratio suggests that the company relies more heavily on debt to fuel growth, which could increase financial risk, especially during economic downturns when managing debt obligations becomes more challenging. In contrast, a lower D/E ratio indicates that the company is primarily financed through equity, reducing financial risk but potentially limiting its ability to rapidly expand.

Legendary value investor Warren Buffett generally prefers a debt-to-equity (D/E) ratio below 0.5. Toyota’s D/E ratio, however, stood at approximately 1.57 in 2024. TWhile this could raise concerns about Toyota’s financial leverage and its capacity to manage debt—especially amid industry shifts and economic uncertainties, it is not necessarily a red flag. Toyota has been strategically using debt to fund key investments in electrification, hydrogen technology, and autonomous systems, supporting its long-term growth ambitions. The downwards trend in D/E ratio is also a positive sign for investors as it indicates less reliance on debt financing over the years.

Price to earning ratio (P/E)

Illustration 18 and 19: Price to earnings ratio of Toyota Motor Corp. from 2010 to 2025

For value investors, one of the most critical metrics when evaluating Toyota’s stock is the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, as it helps assess whether the company is undervalued or overvalued. Even if a company has strong financials, purchasing its stock at a high price can lead to poor returns. For example, imagine a business generating solid profits of $1 million per year. If the owner offers to sell you the business for just $1, it would be an incredible deal. But if the owner asks for $1 trillion, even though the business is profitable, the price would be absurdly overvalued. The stock market works similarly, companies can be priced cheaply on some days and excessively expensive on others.

Warren Buffett, a legendary value investor, typically considers stocks with a P/E ratio of 15 or lower as “bargains.” A high P/E ratio suggests that investors are paying a premium for the company’s earnings, expecting significant growth. Toyota Motor Corporation has consistently maintained a relatively low P/E ratio over the years, hovering around 10 across multiple periods, as can be seen in illustration 18. This consistent valuation suggests a cautious but stable investor outlook, reflecting Toyota’s mature industry position and steady earnings performance. The current P/E ratio of 10.2 may signal that Toyota remains undervalued relative to the broader market. For value investors, this steady undervaluation could present an appealing entry point, especially if Toyota continues to perform reliably while transitioning to electric and autonomous vehicle technologies.

Price to Book ratio (P/B)

Illustration 20 and 21: Price to book ratio for Toyota Motor Corp. from 2009 to 2024

Price-to-book value (P/B ratio) is a financial metric used to compare a company’s market value (its stock price) to its book value (the net asset value of the company, calculated as total assets minus total liabilities). The P/B ratio is calculated by dividing the current share price by the book value per share. A lower P/B ratio suggests that the stock may be undervalued, as investors are paying less for the company’s assets than their actual worth. Conversely, a high P/B ratiomay indicate that the stock is overvalued, or that investors expect high growth in the company’s future earnings. The P/B ratio is often used by value investors to assess whether a stock is trading at a fair price based on its underlying assets. Legendary Investor Warren Buffet prefers company’s with P/B lower than 1.5 and often buys around 1.3 or lower.

The price-to-book (P/B) ratio of Toyota Motor Corporation is a green flag for value-oriented investors, as it has remained consistently low compared to industry peers and well within the range Warren Buffett often considers attractive. With a P/B ratio typically hovering around 1.0 or lower in recent years, Toyota appears undervalued relative to the net worth of its assets. This suggests that investors are paying a modest price for ownership in a company with strong tangible asset backing, healthy cash flows, and a proven global presence. Unlike tech companies with inflated P/B ratios driven by future growth speculation, Toyota’s low P/B reflects its stable earnings, conservative balance sheet, and disciplined capital allocation. For value investors, this consistency signals a potentially underappreciated opportunity, especially as Toyota ramps up its transition to electric and hydrogen vehicles, which could unlock new growth while maintaining financial resilience. Rather than indicating market pessimism, Toyota’s low valuation may simply reflect a longstanding investor tendency to undervalue traditional automakers, offering a chance for upside if the market re-rates its future prospects.

Return on Investment (ROI)

Illustration 22 and 23: Return on Investment for Toyota Motor Corp. from 2010 to 2015

For value investors, another essential metric when evaluating Toyota’s stock is Return on Investment (ROI), as it reveals how efficiently the company is using its capital to generate profits. In simple terms, ROI measures how much return a business earns relative to the capital invested to run it. Even if a company shows strong revenues, if it needs massive amounts of capital to produce modest profits, it may not be an attractive investment. For example, if one company generates a $100,000 return on a $1 million investment, while another earns the same return on just $500,000, the latter is clearly more efficient and potentially more valuable. ROI helps investors identify these distinctions and avoid companies that consume capital without delivering proportional returns. The higher the ROI, the better but it is also very industry dependent as some industries need a lot more capital than others. Legendary investor Warren Buffett has often stated that he seeks returns of at least 15% annually on his investments over time. While he doesn’t quote ROI specifically, this is effectively what he aims for in terms of return on invested capital and intrinsic value growth.

Toyota Motor Corporation has historically delivered a low but stable ROI, often ranging between 5% and 10%, which is considered healthy for a capital-intensive industry like automotive manufacturing. Even though, this is under Buffet’s expectations this is a normal ROI in the automaker industry which is very capital intensive. This consistent performance indicates that Toyota is effectively deploying its resources to generate returns, especially in comparison to peers in the same sector who may struggle with slimmer margins or capital inefficiency. As shown in illustration 21, Toyota’s ability to maintain solid ROI over time. despite economic cycles, supply chain disruptions, and shifts in consumer demand, demonstrates sound management and operational resilience. For long-term investors, this level of capital efficiency is a green flag, suggesting that Toyota is not just a stable company but one that continues to deliver meaningful returns without reckless spending, even as it invests in the future of mobility through electrification and automation.

Dividend

Illustration 24: Dividend Yield and dividend payout ratio from 2005 to 2025.

Toyota Motor Corporation has established itself as a reliable dividend payer in the global automotive industry, offering an annual dividend of approximately ¥60–¥70 per share in recent years. This reflects the company’s commitment to rewarding shareholders while maintaining financial discipline. Toyota’s steady dividend history—even through economic downturns—underscores its reputation as a financially stable, conservative company, making it a favorable choice for income-seeking investors.

However, there are considerations regarding Toyota’s dividend yield, which typically ranges between 2% and 3%. While the company continues to return capital to shareholders, growing demands for investment in electrification, autonomous driving, and sustainability initiatives could limit the pace of future dividend increases. As Toyota ramps up R&D and capital expenditures to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving industry, sustained dividend growth may face some headwinds if earnings growth slows.

Insider Trading

As a Foreign Private Issuer (FPI), Toyota is not required to file insider trading reports with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). However, the company provides detailed disclosures in its annual reports and Form 20-F filings, which include information on executive compensation, shareholdings, and related party transactions.

Over the past years, Toyota Motor Corporation has not reported direct insider transactions involving its own shares. According to publicly available data and insider-tracking sources, the most recent direct insider transactions involving Toyota Motor Corporation’s own stock (NYSE: TM) date back to 2004.

This can be seen as both a red and a green flag for potential investors. It is a green flag as The absence of insider sales may suggest that Toyota’s executives have long-term confidence in the company and see no reason to cash out. Unlike many public firms where executives frequently sell stock, Toyota’s leadership appears more focused on stewardship than on short-term financial gains. Furthermore, In Japan, corporate culture traditionally emphasizes stability, loyalty, and modest compensation. Executives are less incentivized through stock grants compared to U.S. firms. This can reflect a conservative, shareholder-friendly philosophy where management is aligned with long-term success rather than short-term speculation.

However, The absence of insider purchases—even during market dips—may raise eyebrows. If executives truly believed the stock was undervalued at any point, why didn’t they buy? In the U.S., insider buying is often considered a strong bullish signal. Toyota is a Japanese company listed as an ADR (American Depositary Receipt) in the U.S., and insider trading disclosures aren’t held to the same real-time standards as in the U.S. This can lead to lower visibility and slower access to critical insider activity data, which some investors view as a governance downside. Toyota’s executive compensation is less tied to equity than U.S. firms, meaning insiders may not have “skin in the game” to the same extent. For some investors, this reduces alignment between management and shareholders.

Other Company Info

Founded in 1937, Toyota Motor Corporation is one of the world’s largest and most respected automotive manufacturers, known for its high quality and sustainable vehicles. As of 2024, Toyota employs approximately 375,000 people globally, reflecting its extensive operations in manufacturing, R&D, and mobility solutions. The company is publicly traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) under the ticker symbol 7203 which is its main listing, but it is also cross -listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol TM and operates within the Consumer Discretionary sector, specifically in the Automobiles industry.

Toyota is headquartered at 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture, Japan. As of 2024, the company has approximately 3.2 billion shares outstanding, with a market capitalization of over $300 billion USD. For more information, visit Toyota’s official website: https://global.toyota.

Final Verdict

Toyota Motor Corporation is a solid long-term investment, especially for value and income investors. With consistently low P/E and P/B ratios, the stock appears undervalued compared to its history and peers. Toyota has a strong balance sheet, steady dividends, and a conservative payout ratio, making it reliable for income seekers.

The company is investing in hybrids, electric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cells, and autonomous driving, maintaining its global leadership with operations in over 170 countries. Although Toyota’s EV transition is slower than some competitors, its diversified approach could offer stability.

Overall, Toyota looks like a great opportunity for value investors. It seems undervalued, has solid financials and offers steady growth nad reliable dividends, making it an attractive choice for long-term investors focused on stability rather than rapid growth.