What Is a Dividend?

A dividend is the distribution of some of a company’s earnings to a class of its shareholders, as determined by the company’s board of directors. Common shareholders of dividend-paying companies are typically eligible as long as they own the stock before the ex-dividend date. Dividends may be paid out as cash or in the form of additional stock or other property. Along with companies, various mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETF) also pay dividends.

A dividend is a token reward paid to the shareholders for their investment in a company’s equity, and it usually originates from the company’s net profits. While the major portion of the profits is kept within the company as retained earnings–which represent the money to be used for the company’s ongoing and future business activities–the remainder can be allocated to the shareholders as a dividend. At times, companies may still make dividend payments even when they don’t make suitable profits. They may do so to maintain their established track record of making regular dividend payments.

The board of directors can choose to issue dividends over various time frames and with different payout rates. Dividends can be paid at a scheduled frequency, such as monthly, quarterly or annually.

Larger, more established companies with more predictable profits are often the best dividend payers. These companies tend to issue regular dividends because they seek to maximize shareholder wealth in ways aside from normal growth. Companies in the following industry sectors are observed to be maintaining a regular record of dividend payments: Basic materials, Oil and gas, Banks and financial, Healthcare and pharmaceuticals and Utilities. Companies structured as master limited partnership (MLP) and real estate investment trust (REIT) are also top dividend payers since their designations require specified distributions to shareholders.

Certain dividend-paying companies may go as far as establishing dividend payout targets, which are based on generated profits in a given year. For example, banks typically pay out a certain percentage of their profits in the form of cash dividends. If profits decline, dividend policy can be postponed to better times.

Start-ups and other high-growth companies, such as those in the technology or biotech sectors, may not offer regular dividends.

Because these companies may be in the early stages of development and may incur high costs (as well as losses) attributed to research and development, business expansion and operational activities, they may not have sufficient funds to issue dividends. Even profit-making early- to mid-stage companies avoid making dividend payments if they are aiming for higher-than-average growth and expansion, and want to invest their profits back into their business rather than paying dividends. The business growth cycle partially explains why growth firms do not pay dividends; they need these funds to expand their operations, build factories and increase their personnel.

Important Dividend Dates

Dividend payments follow a chronological order of events and the associated dates are important to determine the shareholders who qualify for receiving the dividend payment.

- Announcement Date: Dividends are announced by company management on the announcement date, and must be approved by the shareholders before they can be paid. Any change in the expected dividend payment can cause the stock to rise or fall quickly as traders adjust to new expectations. The ex-dividend date and record date will occur after the declaration date. Once a dividend is declared on the announcement date, the company has a legal responsibility to pay it.

- Ex-Dividend Date: The date on which the dividend eligibility expires is called the ex-dividend date or simply the ex-date. For instance, if a stock has an ex-date of Monday, May 5, then shareholders who buy the stock on or after that day will NOT qualify to get the dividend as they are buying it on or after the dividend expiry date. Shareholders who own the stock one business day prior to the ex-date – that is on Friday, May 2, or earlier – will receive the dividend. The value of a share of stock goes down by about the dividend amount when the stock goes ex-dividend.

- Record Date: The record date is the cut-off date, established by the company in order to determine which shareholders are eligible to receive a dividend or distribution.

- Payment Date: The company issues the payment of the dividend on the payment date which is when the money gets credited to investors’ accounts.

The dividend may rise on the announcement approximately by the amount of the dividend declared and then decline by a similar amount at the opening session of the ex-dividend date.

For example, a company that is trading at $50 per share declares a $5 dividend on the announcement date. As soon as the news becomes public, the share price shoots up by around $5 and hit $55. Say the stock trades at $52 one business day prior to the ex-dividend date. On the ex-dividend date, it comes down by a similar $5 and begins trading at $50 at the start of the trading session on the ex-dividend date, because anyone buying on the ex-dividend date will not receive the dividend.

Why companies pay dividend

Companies pay dividends for a variety of reasons. Dividends can be expected by the shareholders as a reward for their trust in a company. The company management may aim to honor this sentiment by delivering a robust track record of dividend payments. Dividend payments reflect positively on a company and help maintain investors’ trust.

A high-value dividend declaration can indicate that the company is doing well and has generated good profits. But it can also indicate that the company does not have suitable projects to generate better returns in the future. Therefore, it is utilizing its cash to pay shareholders instead of reinvesting it into growth

One of the simplest ways for companies to foster goodwill among their shareholders, drive demand for the stock, and communicate financial well-being and shareholder value is through paying dividends. Paying dividends sends a message about a company’s future prospects and performance. Its willingness and ability to pay steady dividends over time provides a solid demonstration of financial strength. Mature firms that believe they can increase value by reinvesting their earnings will choose not to pay dividends.

If a company has a long history of dividend payments, a reduction of the dividend amount, or its elimination, may signal to investors that the company is in trouble. The announcement of a 50% decrease in dividends from General Electric Co. (GE), one of the biggest American industrial companies, was accompanied by a decline of more than six percent in GE’s stock price on November 13, 2017.

A reduction in dividend amount or a decision against making any dividend payment may not necessarily translate into bad news about a company. It may be possible that the company’s management has better plans for investing the money, given its financials and operations. For example, a company’s management may choose to invest in a high-return project that has the potential to magnify returns for shareholders in the long run, as compared to the petty gains they will realize through dividend payments.

It could be when the pricing and conditions are just right for a stock buyback; weathering a major recession becomes the priority; or a company needs to accumulate cash on hand for a big merger or acquisition.

Forms of dividend

A cash dividend is a payment doled out by a company to its stockholders in the form of periodic distributions of cash. Most brokers offer a choice to accept or reinvest cash dividends; reinvesting dividends is often a smart choice for investors with a long-term focus.

A stock dividend is a dividend payment to shareholders that is made in shares rather than as cash. The stock dividend has the advantage of rewarding shareholders without reducing the company’s cash balance, although it can dilute earnings per share. This type of dividend may be made when a company wants to reward its investors but doesn’t have the spare cash or wants to preserve its cash for other investments. This, however, like the cash dividend, does not increase the value of the company. If the company was priced at $10 per share, the value of the company would be $10 million. After the stock dividend, the value will remain the same, but the share price will decrease to $9.52 to adjust for the dividend payout.

Stock dividends can have a negative impact on share price in the short-term. Because it increases the number of shares outstanding while the value of the company remains stable, it dilutes the book value per common share, and the stock price is reduced accordingly.

Fund Dividends v. Company dividends

Dividends paid by funds are different from dividends paid by companies. Company dividends are usually paid from profits that are generated from the company’s business operations. Funds work on the principle of net asset value (NAV), which reflects the valuation of their holdings or the price of the asset(s) that a fund may be tracking. Since funds don’t have any intrinsic profits, they pay dividends sourced from their NAV.

Due to the NAV-based working of funds, regular and high-frequency dividend payments should not be misunderstood as a stellar performance by the fund. For example, a bond-investing fund may pay monthly dividends as it receives money in the form of monthly interest on its interest-bearing holdings. The fund is merely transferring the income from the interest fully or partially to the fund investors. A stock-investing fund may also pay dividends. Its dividends may come from the dividend(s) it receives from the stocks held in its portfolio, or by selling a certain quantity of stocks. It’s likely the investors receiving the dividend from the fund are reducing their holding value, which gets reflected in the reduced NAV on the ex-dividend date.

Arguments Against Dividends

Some financial analyst believe that the consideration of a dividend policy is irrelevant because investors have the ability to create “homemade” dividends. These analysts claim that income is achieved by investors adjusting their asset allocation in their portfolios.

For example, investors looking for a steady income stream are more likely to invest in bonds where the interest payments don’t fluctuate, rather than a dividend-paying stock, where the underlying price of the stock can fluctuate. As a result, bond investors don’t care about a particular company’s dividend policy because their interest payments from their bond investments are fixed.

Another argument against dividends claims that little to no dividend payout is more favorable for investors. Supporters of this policy point out that taxation on a dividend is higher than on a capital gain (In the US). The argument against dividends is based on the belief that a company which reinvests funds (rather than paying them out as dividends) will increase the value of the company in the long-term and, as a result, increase the market value of the stock. According to proponents of this policy, a company’s alternatives to paying out excess cash as dividends are the following: undertaking more projects, repurchasing the company’s own shares, acquiring new companies and profitable assets, and reinvesting in financial assets.

Arguments for Dividends

Proponents of dividends point out that a high dividend payout is important for investors because dividends provide certainty about the company’s financial well-being. Typically, companies that have consistently paid dividends are some of the most stable companies over the past several decades. As a result, a company that pays out a dividend attracts investors and creates demand for their stock.

Dividends are also attractive for investors looking to generate income. However, a decrease or increase in dividend distributions can affect the price of a security. The stock prices of companies that have a long-standing history of dividend payouts would be negatively affected if they reduced their dividend distributions. Conversely, companies that increased their dividend payouts or companies that instituted a new dividend policy would likely see appreciation in their stocks. Investors also see a dividend payment as a sign of a company’s strength and a sign that management has positive expectations for future earnings, which again makes the stock more attractive. A greater demand for a company’s stock will increase its price. Paying dividends sends a clear, powerful message about a company’s future prospects and performance, and its willingness and ability to pay steady dividends over time provides a solid demonstration of financial strength.

Dividend-Paying Methods:

Companies that decide to pay a dividend might use one of the three methods outlined below.

1. Residual

Companies using the residual dividend policy choose to rely on internally generated equity to finance any new projects. As a result, dividend payments can come out of the residual or leftover equity only after all project capital requirements are met.

The benefits to this policy is that it allows a company to use their retained earnings or residual income to invest back into the company, or into other profitable projects before returning funds back to shareholders in the form of dividends.

As stated earlier, a company’s stock price fluctuates with a rising or falling dividend. If a company’s management team doesn’t believe they can adhere to a strict dividend policy with consistent payouts, it might opt for the residual method. The management team is free to pursue opportunities without being constricted by a dividend policy. However, investors might demand a higher stock price relative to companies in the same industry that have more consistent dividend payouts. Another drawback to the residual method is that it can lead to inconsistent and sporadic dividend payouts resulting in volatility in the company’s stock price.

2. Stable

Under the stable dividend policy, companies consistently pay a dividend each year regardless of earnings fluctuations. The dividend payout amount is typically determined through forecasting long-term earnings and calculating a percentage of earnings to be paid out.

Under the stable policy, companies may create a target payout ratio, which is a percentage of earnings that is to be paid to shareholders in the long-term.

The company may choose a cyclical policy that sets dividends at a fixed fraction of quarterly earnings, or it may choose a stable policy whereby quarterly dividends are set at a fraction of yearly earnings. In either case, the aim of the stability policy is to reduce uncertainty for investors and to provide them with income.

3. Hybrid

The final approach combines the residual and stable dividend policies. The hybrid is a popular approach for companies that pay dividends. As companies experience business cycle fluctuations, companies that use the hybrid approach establish a set dividend, which represents a relatively small portion of yearly income and can be easily maintained. In addition to the set dividend, companies can offer an extra dividend paid only when income exceeds certain benchmarks.

Is Dividend Investing a Good Strategy?

Investors should be aware of extremely high yields, since there is an inverse relationship between stock price and dividend yield and the distribution might not be sustainable. Stocks that pay dividends typically provide stability to a portfolio, but do not usually outperform high-quality growth stocks.

It may be counter-intuitive, but as a stock’s price increases, its dividend yield actually decreases. Dividend yield is a ratio of how much cash flow you are getting for each dollar invested in a stock. Many novice investors may incorrectly assume that a higher stock price correlates to a higher dividend yield. Let’s delve into how dividend yield is calculated, so we can grasp this inverse relationship.

If you own 100 shares of the ABC Corporation, the 100 shares is your basis for dividend distribution. Assume for the moment that ABC Corporation was purchased at $100 per share, which implies a total investment of $10,000. Profits at the ABC Corporation were unusually high, so the board of directors agrees to pay its shareholders $10 per share annually in the form of a cash dividend. So, as an owner of ABC Corporation for a year, your continued investment in ABC Corp result in $1,000 dollars of dividends. The annual yield is the total dividend amount ($1,000) divided by the cost of the stock ($10,000) which equals 10 percent.

If ABC Corporation was purchased at $200 per share instead, the yield would drop to five percent, since 100 shares now costs $20,000 (or your original $10,000 only gets you 50 shares, instead of 100). As illustrated above, if the price of the stock moves higher, then dividend yield drops and vice versa. From an investment strategy perspective, buying established companies with a history of good dividends adds stability to a portfolio. This is why many investing legends such as John Bogle, Warren Buffet and Benjamin Graham advocate buying stocks that pay dividends as a critical part of the total “investment” return of an asset.

The Risks to Dividends

During the 2008-2009 financial crisis, almost all of the major banks either slashed or eliminated their dividend payouts. These companies were known for consistent, stable dividend payouts each quarter for literally hundreds of years. Despite their storied histories, many dividends were cut.

In other words, dividends are not guaranteed, and are subject to macroeconomic as well as company-specific risks. Another potential downside to investing in dividend-paying stocks is that companies that pay dividends are not usually high-growth leaders. There are some exceptions, but high-growth companies usually do not pay sizable amounts of dividends to its shareholders even if they have significantly outperformed the vast majority of stocks over time. Growth companies tend to spend more dollars on research and development, capital expansion, retaining talented employees and/or mergers and acquisitions. For these companies, all earnings are considered retained earnings, and are reinvested back into the company instead of issuing a dividend to shareholders.

It is equally important to beware of companies with extraordinarily high yields. As we have learned, if a company’s stock price continues to decline, its yield goes up. Many rookie investors get teased into purchasing a stock just on the basis of a potentially juicy dividend. There is no specific rule of thumb in relation to how much is too much in terms of a dividend payout.

The average dividend yield on S&P 500 index companies that pay a dividend historically fluctuates somewhere between 2 and 5 percent, depending on market conditions. In general, it pays to do your homework on stocks yielding more than 8 percent to find out what is truly going on with the company. Doing this due diligence will help you decipher those companies that are truly in financial shambles from those that are temporarily out of favor, and therefore present a good investment value proposition.

Once a company starts paying dividends, it is highly atypical for it to stop. Dividends are a good way to give an investment portfolio additional stability, since the periodical cash payments are likely to continue long term.

A company must keep growing at an above-average pace to justify reinvesting in itself rather than paying a dividend. Generally speaking, when a company’s growth slows, its stock won’t climb as much, and dividends will be necessary to keep shareholders around. The slowdown of this growth happens to virtually all companies after they attain a large market capitalization. A company will simply reach a size at which it no longer has the potential to grow at annual rates of 30% to 40%, like a small cap, regardless of how much money is plowed back into it. At a certain point, the law of large numbers makes a mega-cap company and growth rates that outperform the market an impossible combination.

There is another motivation for a company to pay dividends —a steadily increasing dividend payout is viewed as a strong indication of a company’s continuing success. The great thing about dividends is that they can’t be faked; they are either paid or not paid, increased or not increased.

This isn’t the case with earnings, which are basically an accountant’s best guess of a company’s profitability. All too often, companies must restate their past reported earnings because of aggressive accounting practices, and this can cause considerable trouble for investors, who may have already based future stock price predictions on these unreliable historical earnings. Expected groeth rates are also unreliable

Since they can be regarded as quasi-bonds, dividend-paying stocks tend to exhibit pricing characteristics that are moderately different from those of growth stocks. This is because they provide regular income that is similar to a bond, but they still provide investors with the potential to benefit from share price appreciation if the company does well.

Investors looking for exposure to the growth potential of the equity market and the safety of the (moderately) fixed income provided by dividends should consider adding stocks with high dividend yields to their portfolio. A portfolio with dividend-paying stocks is likely to see less price volatility than a growth stock portfolio.

Misconceptions About Dividend Stocks

The biggest misconception of dividend stocks is that a high yield is always a good thing. Many dividend investors simply choose a collection of the highest dividend-paying stock and hope for the best. For a number of reasons, this is not always a good idea.

Dividend Stocks are Always Boring. Some of the best traits a dividend stock can have are the announcement of a new dividend, high dividend growth metrics over recent years, or the potential to commit more and raise the dividend (even if the current yield is low). Any of these announcements can jolt the stock price and result in a greater total return. Sure, trying to predict management’s dividends and whether a dividend stock will go up in the future is not easy, but there are several indicators. If a stock has a low dividend payout ratio but it is generating high levels of free cash flow, it obviously has room to increase its dividend. Earnings growth is one indicator but also keep an eye on cash flow and revenues as well. If a company is growing organically (i.e. increased foot traffic, sales, margins), then it may only be a matter of time before the dividend is increased. However, if a company’s growth is coming from high-risk investments or international expansion then a dividend could be less certain

Dividend Stocks are Always Safe. Just because a company is producing dividends doesn’t always make it a safe bet. Management can use the dividend to placate frustrated investors when the stock isn’t moving. (In fact, many companies have been known to do this.) Therefore, to avoid dividend traps, it’s always important to at least consider how management is using the dividend in its corporate strategy. Dividends that are consolation prizes to investors for a lack of growth are almost always bad ideas.

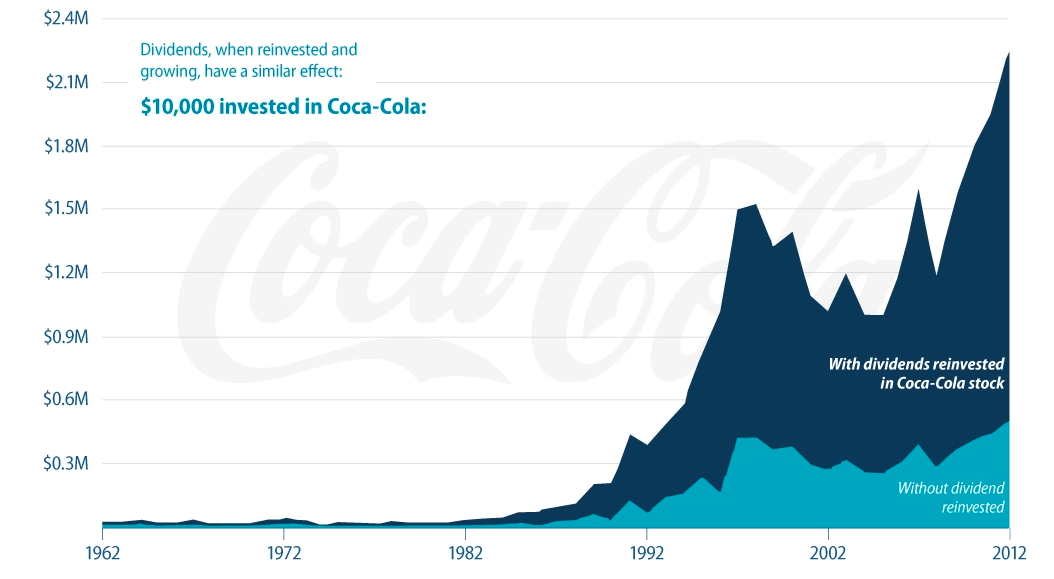

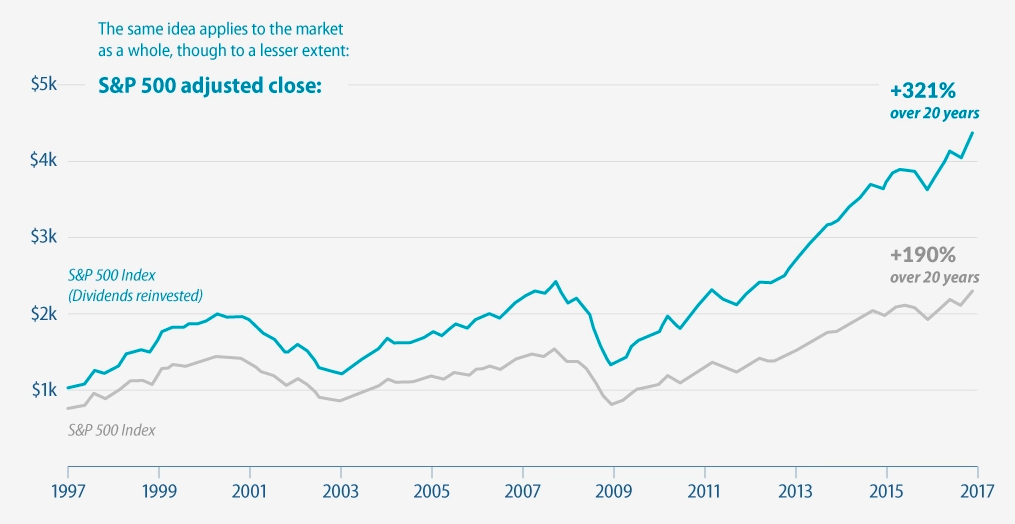

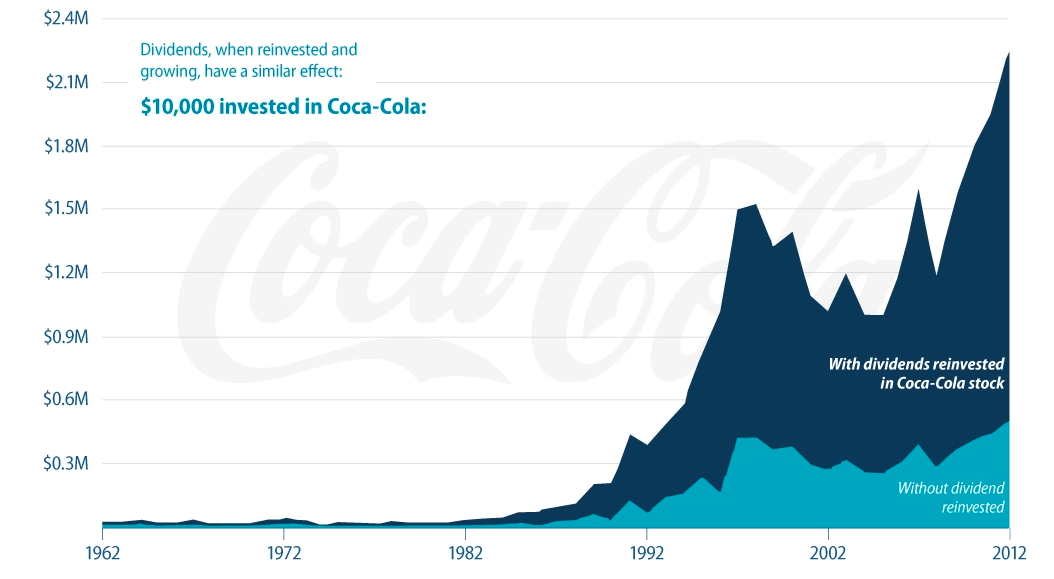

Compounding Effect

If dividends are re-invested it can create a compounding effect as show in the graphs below gathered from visualcapitalist.

Figures retrieved from https://www.visualcapitalist.com/power-dividend-investing/

Dividend Yield

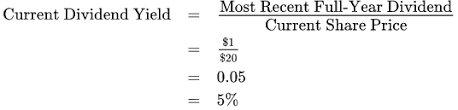

The dividend yield, expressed as a percentage, is a financial ratio (dividend/price) that shows how much a company pays out in dividends each year relative to its stock price.

The dividend yield is an estimate of the dividend-only return of a stock investment. Assuming the dividend is not raised or lowered, the yield will rise when the price of the stock falls. Because dividend yields change relative to the stock price, it can often look unusually high for stocks that are falling in value quickly.

Figure retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dividend_yield

The dividend yield can be calculated from the last full year’s financial report. This is acceptable during the first few months after the company has released its annual report; however, the longer it has been since the annual report, the less relevant that data is for investors. Alternatively, investors can also add the last four quarters of dividends, which captures the trailing 12 months of dividend data. Using a trailing dividend number is acceptable, but it can make the yield too high or too low if the dividend has recently been cut or raised.

Because dividends are paid quarterly, many investors will take the last quarterly dividend, multiply it by four, and use the product as the annual dividend for the yield calculation. This approach will reflect any recent changes in the dividend, but not all companies pay an even quarterly dividend. Some firms, especially outside the U.S., pay a small quarterly dividend with a large annual dividend. If the dividend calculation is performed after the large dividend distribution, it will give an inflated yield. Finally, some companies pay a dividend more frequently than quarterly. A monthly dividend could result in a dividend yield calculation that is too low. When deciding how to calculate the dividend yield, an investor should look at the history of dividend payments to decide which method will give the most accurate results.

Historical evidence suggests that a focus on dividends may amplify returns rather than slow them down. For example, according to analysts at Hartford Funds, since 1970, 78% of the total returns from the S&500 are from dividends. This assumption is based on the fact that investors are likely to reinvest their dividends back into the S&P 500, which then compounds their ability to earn more dividends in the future.

When comparing measures of corporate dividends, it’s important to note that the dividend yield tells you what the simple rate of return is in the form of cash dividends to shareholders. However, the dividend payout ratio represents how much of a company’s net earnings are paid out as dividends. While the dividend yield is the more commonly used term, many believe the dividend payout ratio is a better indicator of a company’s ability to distribute dividends consistently in the future. The dividend payout ratio is highly connected to a company’s cash flow.

The dividend yield shows how much a company has paid out in dividends over the course of a year. The yield is presented as a percentage, not as an actual dollar amount. This makes it easier to see how much return the shareholder can expect to receive per dollar they have invested.

A forward dividend yield is the percentage of a company’s current stock price that it expects to pay out as dividends over a certain time period, generally 12 months. Forward dividend yields are generally used in circumstances where the yield is predictable based on past instances. If not, trailing yields, which indicate the same value over the previous 12 months, are used.

Figure retrieved from https://www.visualcapitalist.com/power-dividend-investing/

A dividend aristocrat is a company that has increased its dividends for at least 25 consecutive years.

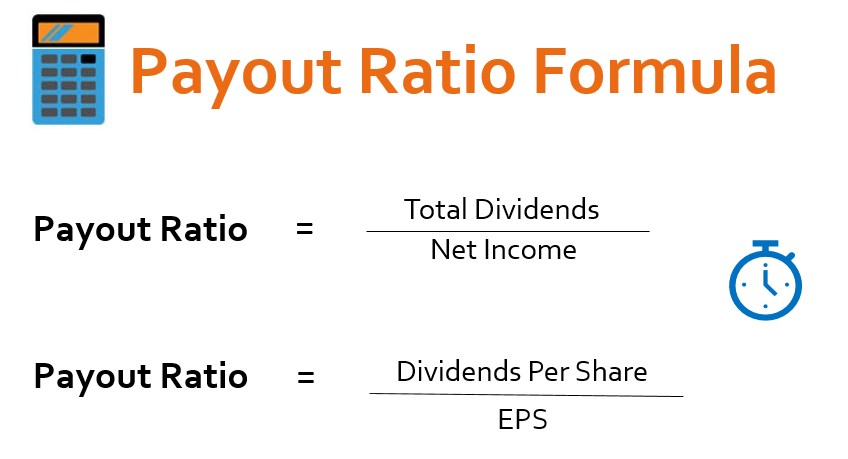

Dividend Payout Ratio

The dividend payout ratio is the ratio of the total amount of dividends paid out to shareholders relative to the net income of the company. It is the percentage of earnings paid to shareholders in dividends. The amount that is not paid to shareholders is retained by the company to pay off debt or to reinvest in core operations. It is sometimes simply referred to as the ‘payout ratio.’

The dividend payout ratio provides an indication of how much money a company is returning to shareholders versus how much it is keeping on hand to reinvest in growth, pay off debt, or add to cash reserves (retained earnings).

Retrieved from https://www.educba.com/payout-ratio-formula/

Dividend Payout Ratio=1−Retention Ratio

Retention Ratio=(EPS−DPS)/EPS

Some companies pay out all their earnings to shareholders, while some only pay out a portion of their earnings. If a company pays out some of its earnings as dividends, the remaining portion is retained by the business. To measure the level of earnings retained, the retention ratio is calculated.

Several considerations go into interpreting the dividend payout ratio, most importantly the company’s level of maturity. A new, growth-oriented company that aims to expand, develop new products, and move into new markets would be expected to reinvest most or all of its earnings and could be forgiven for having a low or even zero payout ratio. The payout ratio is 0% for companies that do not pay dividends and is 100% for companies that pay out their entire net income as dividends.

The payout ratio is also useful for assessing a dividend’s sustainability. Companies are extremely reluctant to cut dividends since it can drive the stock price down and reflect poorly on management’s abilities. If a company’s payout ratio is over 100%, it is returning more money to shareholders than it is earning and will probably be forced to lower the dividend or stop paying it altogether. That result is not inevitable, however. A company endures a bad year without suspending payouts, and it is often in their interest to do so. It is therefore important to consider future earnings expectations and calculate a forward-looking payout ratio to contextualize the backward-looking one.

Long-term trends in the payout ratio also matter. A steadily rising ratio could indicate a healthy, maturing business, but a spiking one could mean the dividend is heading into unsustainable territory.

The retention ratio is a converse concept to the dividend payout ratio. The dividend payout ratio evaluates the percentage of profits earned that a company pays out to its shareholders, while the retention ratio represents the percentage of profits earned that are retained by or reinvested in the company.

Dividend payouts vary widely by industry, and like most ratios, they are most useful to compare within a given industry

The augmented payout ratio incorporates share buybacks into the metric; it is calculated by dividing the sum of dividends and buybacks by net income for the same period. If the result is too high, it can indicate an emphasis on short-term boosts to share prices at the expense of reinvestment and long-term growth. Another adjustment that can be made to provide a more accurate picture is to subtract preferred stock dividends for companies that issue preferred shares.

Dividends Per Share

Dividends per share (DPS) measures the total amount of profits a company pays out to its shareholders, generally over a year, on a per-share basis. DPS can be calculated by subtracting the special dividends from the sum of all dividends over one year and dividing this figure by the outstanding shares

Retrieved from https://www.tickertape.in/glossary/dividend-per-share-meaning/

There are two primary reasons for increases in a company’s dividends per share payout.

- The first is simply an increase in the company’s net profits out of which dividends are paid. If the company is performing well and cash flows are improving, there is more room to pay shareholders higher dividends. In this context, a dividend hike is a positive indicator of company performance.

- The second reason a company might hike its dividend is because of a shift in the company’s growth strategy, which leads the company to expend less of its cash flow and earnings on growth and expansion, thus leaving a larger share of profits available to be returned to equity investors in the form of dividends.

Dividend Growth Rate

Dividend growth calculates the annualized average rate of increase in the dividends paid by a company. Calculating the dividend growth rate is necessary for using a dividend discount model for valuing stocks. The dividend discount model is a type of security-pricing model. The dividend discount model assumes that the estimated future dividends–discounted by the excess of internal growth over the company’s estimated dividend growth rate–determines a given stock’s price. If the dividend discount model procedure results in a higher number than the current prize of a company’s shares, the model considers the stock undervalued. Investors who use the dividend discount model believe that by estimating the expected value of cash flow in the future, they can find the intrinsic value of a specific stock. A history of strong dividend growth could mean future dividend growth is likely, which can signal long-term profitability.

Dividend capture strategy

A dividend capture strategy is a timing-oriented investment strategy involving the timed purchase and subsequent sale of dividend-paying stocks. Dividend capture is specifically calls for buying a stock just prior to the ex-dividend date in order to receive the dividend, then selling it immediately after the dividend is paid.The purpose of the two trades is simply to receive the dividend, as opposed to investing for the longer term. Because markets tend to be somewhat efficient, stocks usually decline in value immediately following ex-dividend, the viability of this strategy has come into question.

Theoretically, the dividend capture strategy shouldn’t work. If markets operated with perfect logic, then the dividend amount would be exactly reflected in the share price until the ex-dividend date, when the stock price would fall by exactly the dividend amount. Since markets do not operate with such mathematical perfection, it doesn’t usually happen that way. Most often, a trader captures a substantial portion of the dividend despite selling the stock at a slight loss following the ex-dividend date. A typical example would be a stock trading at $20 per share, paying a $1 dividend, falling in price on the ex-date only down to $19.50, which enables a trader to realize a net profit of $0.50, successfully capturing half the dividend in profit.

Transaction costs further decrease the sum of realized returns. The potential gains from a pure dividend capture strategy are typically small, while possible losses can be considerable if a negative market movement occurs within the holding period. A drop in stock value on the ex-date which exceeds the amount of the dividend may force the investor to maintain the position for an extended period of time, introducing systematic and company-specific risk into the strategy. Adverse market movements can quickly eliminate any potential gains from this dividend capture approach. In order to minimize these risks, the strategy should be focused on short term holdings of large blue-chip companies. If dividend capture was consistently profitable, computer-driven investment strategies would have already exploited this opportunity.

Analysis Check

- Notable dividend: Is the companies dividend notable compared to the bottom 25% of dividend players in the country’s(eg. Norwegian) market.

- High dividend: How does the companies dividend compare to the top 25% of dividend players in the country’s market.

- Stable dividend: Have the dividend payments been stable in the past 10 years

- Growing dividend: Have the dividend payments grown over the last 10 years.

- Dividend coverage: Are the dividend covered by the earnings. Look at payout ratio.

- Future dividend coverage: is the dividend forecasted to be covered by earnings in three years? Look at payout ratio.

Warren Buffet Advice: