Introduction

Let’s begin with a riddle worthy of a Wall Street sommelier. If I offered you a case of Château Lafite Rothschild 1982, or the same amount of money in Bitcoin back in 2013… which would you take?

Most people, blinded by the glittering promise of digital gold, would have grabbed the Bitcoin faster than a day trader on caffeine. But here’s the twist: that same 1982 Lafite has outperformed most crypto returns and with far less volatility, drama, or risk of getting hacked by a guy named “CryptoBro69.”

While the world was busy making memes about Dogecoin and diamond hands, a quiet army of cork-sniffing investors was building wealth the old-fashioned way, through grapes, patience, and a touch of French snobbery.

What is Wine Investing?

At its core, wine investing means buying bottles (or cases) of fine wine not to drink (tragic, I know) but to sell later at a profit. You’re not just buying alcohol; you’re buying liquid art that matures in value as it matures in flavor.

But let’s make something clear from the start:

Wine investing is not about getting drunk. It’s about letting your money age beautifully while you resist the temptation to open your assets at dinner .So, you’re not the guy pouring a $2,000 bottle at a barbecue, you’re the one who sells it to him ten years later.

Illustration 1: Red Cabarnet Sauvignong being enjoyed.

The Holy Trinity of Wine Investing

If the world of fine wine were a stock market, then the three regions Bordeaux, Burgundy, and the Rebels Who Sparkle would be its NASDAQ, S&P 500, and Dow Jones, except the CEOs are vineyards, the dividends come in liquid form, and the shareholders occasionally get drunk.

If the world of fine wine were a stock market, then the three regions Bordeaux, Burgundy, and the Rebels Who Sparkle would be its NASDAQ, S&P 500, and Dow Jones, except the CEOs are vineyards, the dividends come in liquid form, and the shareholders occasionally get drunk.

Illustration 2: A wine collection can be just as thrilling as the stock market.

Every serious wine investor, from billionaire collectors to humble newcomers storing their first bottle under the bed, eventually discovers that almost all of the world’s most valuable wines come from one of three great tribes: Bordeaux, Burgundy, and the Rest of the Rebels (which includes Champagne, Napa, Tuscany, and a few sneaky new challengers).

- Bordeaux

If wine were a person, Bordeaux would be the old-money aristocrat who lives in a chateau with more history than your entire family tree. He doesn’t need to show off, he’s been rich since the 18th century. Bordeaux is the granddaddy of investment wines, accounting for over 60% of the global fine wine market by value. This is where the concept of “wine as an asset” was practically invented.

In the 1850s, Napoleon III decided France needed to show off at the Paris Exposition, so he asked wine merchants to rank their best producers. The result? The 1855 Bordeaux Classification, the original “wine stock index.”

It divided estates into “First Growths” (the crème de la crème) and lower tiers, and to this day, that list still dictates prices like aristocratic birthrights that refuse to expire. The First Growths (aka Premiers Crus) are: Château Lafite Rothschild, Château Latour, Château Margau, Château Haut-Brion, Château Mouton Rothschild (which had to wait until 1973 to be promoted). These are the blue-chip stocks of the wine world, steady, prestigious, and globally recognized. When someone says “fine wine,” they’re usually talking about one of these.

Illustration 3: Bordeaux wine region with its historic Château, here Château Pichon Longueville Baron in Pauillac, Médoc.

Investors love Bordeaux because it is predictable and has historically provided 8–12% annualised growth over decades. Furthermore, it is liquid as it is the most traded region on Liv-ex, the London International Vintners Exchange. You can buy and sell cases like Apple shares.

These estates make thousands of cases, ensuring enough supply to build a tradable market. Bordeaux wines can age gracefully for 30–50 years. That’s not a bottle, that’s a generational trust fund.

Bordeaux is traditional. Sometimes painfully so. The market can feel slow to adapt. It’s cyclical: Asian demand booms can send prices skyrocketing, followed by hangovers (literally and figuratively). Some vintages are “sleepers” for decades before waking up in auction value. Bordeaux is your grandfather’s portfolio, boring to the impatient, brilliant to the patient. It’s the slow compounding of oak, tannins, and time.

2. Burgundy

If Bordeaux is a tuxedo, Burgundy is a turtleneck, a paintbrush, and a chaotic love life. This is the Picasso of the wine world, complex, emotional, unpredictable, and occasionally insane.

Burgundy wines come mostly from Pinot Noir (reds) and Chardonnay (whites), but what makes them special isn’t the grape, it’s the terroir (that mystical French word meaning “the soul of the soil”).

If Bordeaux is a tuxedo, Burgundy is a turtleneck, a paintbrush, and a chaotic love life. This is the Picasso of the wine world, complex, emotional, unpredictable, and occasionally insane.

Illustration 4: A wine field in Burgundy, France with its classical historic cities in the backgorund.

Burgundy wines come mostly from Pinot Noir (reds) and Chardonnay (whites), but what makes them special isn’t the grape, it’s the terroir (that mystical French word meaning “the soul of the soil”).

Illustration 5: Chardonnay grapes in Burgundy.

Each tiny plot of land produces wine with a slightly different character, and the French have documented these plots for centuries. The result? Micro-production.

Illustration 5: Grapes being collected on a classical small land plot in Burgundy.

Where a Bordeaux estate might make 20,000 cases, a top Burgundy producer might make 400. That’s not scarcity, that’s emotional terrorism for collectors. The most expensive Burgundy is the Domaine de la Romanee-Conti (DRC). Each bottle costs anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000+, and even at those prices, buyers have to beg for allocations.

Investors love Burgumdy bevause it is extremily rare, small plots means small supply. The demand is explosive: Asia, America, and Europe all fight for the same few hundred cases. Furthermore, Burgundy often moves independently of Bordeaux, giving portfolio diversification. It has also a cult power as collectors treat it like fine art, emotional, irrational, and unstoppable.

However, investors should be for a lookout for fakes as Burgundy has been counterfeited more than Gucci bags. It is wildly volatile, one bad harvest and prices can triple overnight. The market is also opaque, prices are private and allocations secretive.

Burgundy is not for the faint-hearted investor. It’s not even for the sober one. But for those who get it right, the returns are mythic. From 2005–2023, top Burgundy labels rose over 600%, beating even Bitcoin (and with fewer crypto bros).

3. The Rebels

Now we come to the fun part, the mavericks, disruptors, and sparkling daredevils of the wine world. If Bordeaux and Burgundy are the establishment, the Rebels are the startups that don’t care about your French traditions. They come from everywhere: Champagne (France), Napa Valley (USA), Tuscany (Italy), Rhone, Rioja (Spain), Barossa (Australia), Stellenbosch (South-Africa), and beyond.

Illustration 6: Nappa Valley wine estates are the prestigous California competitors to the traditional Bordeaux wines.

Napa is Silicon Valley’s winery cousin: ambitious, loud, and occasionally overpriced. Wines like Screaming Eagle, Harlan Estate, and Opus One have become cult legends, with prices that rival Bordeaux First Growths. The appeal? Strong U.S. collector base, Global recognition and American branding power. Napa is what happens when the “move fast and break things” mentality meets French oak barrels.

Italy’s Super Tuscans, like Sassicaia, Tignanello, and Ornellaia were born out of rebellion. When Italian regulations got too strict, these winemakers said, “Fine, we’ll make our own rules.” And those “rule-breakers” are now among the most bankable fine wines in the world. Super Tuscans combine heritage, flavor, and affordability (relatively speaking). They’re like the dividend stocks of wine investing, consistent and comforting.

Illustration 7: Some Italian wine makers still crush the grapes the traditional way with their feet.

If wine is wealth, Champagne is celebration. It’s both a drink and a status symbol, backed by brands like Dom Pérignon, Cristal, and Krug that make the rich feel richer. Here’s the secret: fine Champagne actually ages and appreciates, especially vintage bottles.A 2008 Dom Pérignon bought for $200 can sell for $400–$600 a decade later. Not bad for something that literally fizzes away. Champagne is the only asset class you can pop open and still call it “research.”

Some new world rising stars are Australia’s Penfolds Grange, Chile’s Almaviva, Argentina’s Catena Zapata, South Africa’s Kanonkop, New Zealand white wine. These wines are still underpriced for now. But as global collectors diversify, the next unicorn bottle might come from somewhere you’d least expect.

Illustration 8: Australia is a rising star and is quickly getting known for both their red and white wine.

The Power of Diversification

Even within wine, diversification matters. Bordeaux gives you stability. Burgundy gives you scarcity. Champagne and New World wines give you growth potential.

A well-balanced wine portfolio might look like this:

- 50% Bordeaux — for stability and liquidity

- 30% Burgundy — for upside potential

- 20% Champagne & Others — for diversification and fun

This way, when Bordeaux takes a nap, Burgundy might explode. When Burgundy cools off, Champagne’s bubbles might carry your returns upward. It’s the same principle as stocks, but with corks instead of tickers.

Historically, Bordeaux dominated trade volumes (60–70%), but in the 2010s, Burgundy began to outperform in value growth.

Then Champagne surged post-2020 as collectors sought luxury and celebration after lockdowns. In essence: Bordeaux = Long-term wealth foundation, Burgundy = Volatile rocket fuel and Champagne & Rebels = Emerging market play. Together, they balance risk, return, and excitement, a portfolio that ages like wisdom in a bottle.

How Wine is priced

You might think wine prices are just fancy guesswork, but there’s real math (and madness) behind them.

Illustration 9: Understanding the factors that determines wine prices is the most important thing an investor can do.

Here’s what affects a bottle’s value:

- Provenance – Can you prove it’s authentic and stored properly?

- Vintage – Weather makes or breaks a wine’s quality.

- Producer Reputation – Some wineries are basically brands, like Louis Vuitton with corks.

- Storage Conditions – A single overheated summer can turn a $5,000 bottle into expensive vinegar.

- Critical Scores – A 100-point rating from Robert Parker or Wine Spectator can double prices overnight.

- Global Demand Cycles – When Chinese billionaires start collecting Lafite, prices erupt like champagne.

Vintage

The first, and arguably most crucial, driver of wine value is vintage quality. A vintage is not just the year printed on the label; it is the entire climatic story of that growing season. Sunlight, rainfall, frost, hailstorms, wind, and heatwaves all leave invisible fingerprints on every grape.

Good Vintages, Exceptional weather leads to grapes that are perfectly balanced in sugar, acidity, and tannin. Wines from these years often become legendary and skyrocket in value decades later.

Mediocre Vintages, some years, Mother Nature hits snooze, and the grapes are “fine but forgettable.” These wines may still be pleasant to drink but often underperform financially. Disastrous Vintages, Frosts in Bordeaux in 1956 or hailstorms in Burgundy can destroy crops. Wine from these years may be rare but uneven, and risk is higher, sometimes rewarded, sometimes punished.

Terroir

Terroir is the French mystical word that every sommelier says with a straight face while stroking their chin. It means the unique combination of soil, slope, climate, and vineyard micro-ecosystem that makes one vineyard’s grapes taste completely different from another’s.

If you own a bottle of Romanée-Conti, you’re not just buying wine, you’re buying the exact 1.8 hectares of clay, limestone, and history that produced it. Terroir matter because of its uniqueness, no two vineyards are exactly alike, this scarcity drives prices.

Illustration 10: Understanding the Terroir meaning the soil, geology, history, limestone, etc. of the wine is crucial for all investors. Here Nebbiolo grapes in Australia.

Legendary terroir creates wines that maintain their character year after year, building brand trust and financial security. Finally, top terroirs are like FANG stocks, everyone wants them and supply is limited. Fun fact: In Burgundy, a single vineyard plot as small as a tennis court can produce fewer than 300 bottles per year. Investors are literally buying the soil in a bottle.

Producer Reputation

Not all wines are created equal and not all producers have the same influence. Reputation is king in fine wine. A vineyard’s name can multiply the value of an ordinary vintage tenfold.

Illustration 11: A wine from Château Lafite Rothschild can double in price based on the name alone.

Château Lafite Rothschild, name alone can double a bottle’s value. Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, cult status creates near-insane demand. Screaming Eagle (Napa), scarcity + hype = auction prices that defy gravity. Investors often treat producer reputation like a credit rating for your liquid assets, the more prestigious, the safer (and pricier) the bet.

Critical Scores

You know how a celebrity tweet can tank a stock? In wine investing, one critic’s score can double or halve a bottle’s price overnight. Robert Parker is Perhaps the most feared and revered critic. His 100-point ratings often create bidding wars.

Wine Spectator & Jancis Robinson is less dramatic, but still market-moving. Decanter & James Suckling are emerging players in modern auctions. For example: A 95-point Lafite may fetch $1,500 at auction but 100-point Lafite the same year? $3,500. Overnight. Investors monitor these ratings like day traders monitor candlestick charts, except there’s no panic selling at 2 a.m., just quiet, patient portfolio adjustments.

Global Demand and Storage

Scarcity is the fuel behind fine wine investing. Limited production means high competition for every bottle, especially in Burgundy or cult Napa wines. Burgundy: Hundreds of bottles per vineyard. Bordeaux First Growths: Thousands, but still finite. Screaming Eagle: Hundreds, sold by lottery.

Supply never increases artificially. Unlike tech companies that can issue new stock, these wines are finite. Once gone, the value often appreciates simply because someone else wants it badly enough.

Illustration 12: The number of wines are finite and as such supply never increases artifically.

Here’s where the sorcery enters. Wine doesn’t just sit around, it transforms, increasing in complexity, aroma, and liquidity. Bordeaux: Peaks in 15–50 years. Burgundy: Peaks in 10–30 years for reds, 5–15 for whites. Champagne: Vintage bubbles can develop in 5–20 years.

Illustration 13: Old wine that has been aging over 100 years

The financial magic is this: a bottle purchased young may increase in value as it ages and becomes drinkable, creating a perfectly time-aligned investment. A case of 2010 Lafite bought for $10,000 might sell for $30,000 when it’s optimally aged at 20 years. The “asset” isn’t just liquid, it’s living.

Illustration 14: Asian women are becoming the new drivers of the wine industry.

Even perfect vintage, terroir, and brand mean nothing if no one wants to buy. Wine is a global, sentiment-driven market: Asia (China, Hong Kong, Singapore) are huge buyers since the 2000s, pushing prices for top Bordeaux and Burgundy into orbit. US: Napa and cult wines dominate. Europe: Bordeaux, Champagne, and Burgundy remain traditional anchors.

Investor psychology here is wild: a rumor of allocation scarcity can spark auctions where bottles sell for 3–5x estimated prices. Fear of missing out is very real, like Black Friday for billionaires.

Provenance

Provenance = history of ownership + storage. It’s the reason you don’t buy a “1959 Lafite” from eBay and expect a profit. Proper storage: Bonded warehouses (temperature and humidity controlled) are crucial.

Chain of ownership: Every hand it’s passed through adds credibility. Documentation: Receipts, labels, and auction records protect against fraud. Without proper provenance, a bottle may be worthless to an investor, no matter how legendary.

Yes, fraud exists and it’s sophisticated. Remember Rudy Kurniawan? He sold millions of dollars’ worth of counterfeit Burgundy and Bordeaux. Always buy from reputable merchants or exchanges.

Check for label integrity, cork markings, and auction documentation. Consider professional authentication services for high-value bottles. The good news: when done right, wine investing is safer than many other collectibles because the community is tight, transparent and highly informed.

Illustration 15: It is crucial to make sure the wine is stored properly.

In practice, a fine wine’s value is an equation with at least ten variables. It’s part science, part art, part magic, and part gambler’s intuition, but unlike Vegas, the odds can be understood, managed, and mastered with patience.

How wine beats inflation

Imagine this: it’s 2030. Inflation is at 8%. Your cash in the bank has lost almost a tenth of its value in a single year. Stocks are volatile. Bonds are yawning.

And yet… your 2010 Lafite Rothschild? That same case that cost you $10,000 is now worth $22,000. And it didn’t just survive, it thrived. Welcome to the liquid hedge against stupidity in monetary policy.

Illustration 16: Wine has been around since ancient times, here an illustration from ancient Greece.

Wine is real. You can touch it, see it, and yes, eventually smell it. Unlike money in the bank, or even ETFs, wine is not an abstract number on a screen. Its scarcity is physical, a finite number of bottles exist, and they age in value like a slow-growing oak tree.

Bordeaux: Large production, steady appreciation. Burgundy: Rare, volatile, but sky-high growth potential. Champagne and cult wines: Emerging, sometimes underrated, but consistently buoyed by celebration and culture. When inflation erodes currency, these bottles hold intrinsic value, collectors will always pay for scarcity and prestige.

During the 2008 Financial Crisis, while the S&P 500 dropped 38%, the Liv-ex Fine Wine 1000 Index rose nearly 25%. In other words, wine investing: countercyclical by accident, profitable by design.

Why? Because: Collectors don’t panic sell. They wait. Fine wine is scarce. Supply never increases overnight. Luxury assets tend to gain value during uncertainty as a safe store of wealth. In periods of global uncertainty, Brexit, U.S. financial turbulence, pandemics, top wines have protected and increased capital, unlike volatile equities.

Wine works as an inflation hedge because people love it irrationally. It’s not just alcohol, it’s status, culture, nostalgia, and sometimes just an excuse to show off in Hong Kong auction rooms.

Illustration 17: Wine has been part of social gatherings for centuries, here from ancient Rome.

Investors in wine aren’t looking at yield curves, they’re chasing prestige, scarcity and the aura of owning something legendary.

For example, a 1982 Château Mouton Rothschild may sell for $40,000 per case, not because it’s “necessary,” but because everyone else wants it or a vintage Dom Pérignon often appreciates even if champagne consumption slows because the global elite view it as an eternal status symbol.

How to Actually Start Investing in Wine?

So you’ve learned about the magic of wine, the trinity of Bordeaux, Burgundy, and Champagne, and maybe even how a bottle can survive inflation better than a checking account. Now comes the big question, how do you actually start investing in wine without turning your apartment into a sticky, overpriced cellar?

Illustration 18: Investor can easily invest in wine through their phones today

Wine investing is simultaneously thrilling, complicated, and occasionally terrifying. It is a world where spreadsheets meet tasting notes, where Bloomberg charts collide with the smell of oak and fermentation, and where a single phone app can change your portfolio faster than a barrel-fermenting Chardonnay.

This is your Investor’s Toolkit, the complete guide to starting smart, avoiding rookie mistakes, and navigating the new digital wine frontier.

Decide on Investment style

First of all you have to decide on your investment style. Not all wine investors are created equal. Some are traditionalists who prefer the tactile thrill of holding a freshly delivered case of Bordeaux in their hands. Others prefer a hands-off approach, letting digital platforms do the heavy lifting while they sip and scroll. Your first task is to define your style:

Illustration 19: Wine jugs from ancient Rome

Hands-On Collector: This is the classic wine investor archetype. You buy full cases directly from reputable merchants, store them in a proper cellar or bonded warehouse, and track them like a cherished pet. The appeal is obvious: complete control. You choose the vintages, manage the storage, and experience the visceral satisfaction of physically owning your assets. The downside? It’s labor-intensive, expensive, and sometimes anxiety-inducing when you realize one rogue heatwave or earthquake could ruin years of careful selection.

Fractional Investor: The new wave. Fractional ownership allows you to own a portion of high-value bottles or even cases without paying for the entire cost upfront. Platforms like Vinovest, Cult Wines, and Vint have democratized the wine market. You don’t need to spend $50,000 to own a Domaine de la Romanée-Conti; you can own a fraction of it for a few thousand dollars. These apps handle storage, provenance verification, and even auction sales for you, making wine investment almost as easy as buying an ETF, but far more intoxicating.

Illustration 19: Vinovest one of these apps that allows investors to invest online.

Auction Aficionado: If you enjoy adrenaline as much as tannins, this style is for you. Hunting legendary vintages on Sotheby’s, Christie’s, or Zachys requires nerves of steel and a thick wallet. Auctions are exhilarating: paddles go up, hearts race and prices can triple in a matter of minutes. But caution: the market is less predictable, fees are high, and emotional buying can destroy your returns faster than a corked bottle.

Wine Fund Participant: For those who want professional management, wine funds pool investor money to create diversified portfolios of fine wine. These funds often include a mix of Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, and emerging New World wines. They also manage storage, insurance, and eventual sale, letting you enjoy returns without handling corks, spreadsheets, or delivery tracking. The catch? Fees are higher, and you give up some control over the individual bottles.

Illustration 20: Patience is important when investing in Wine

Budget and Time Horizon

Wine investing is not a sprint. It is the slow, satisfying marathon where patience is your most valuable asset. You can’t expect to buy a 2010 Lafite and flip it next week for life-changing returns. Top wines appreciate over years, decades even.

Illustration 21: There are different entry levels when it comes to investing in wine.

Entry-Level Investor: $5,000–$10,000 is enough to start building a small, meaningful portfolio. You won’t be a DRC baron, but you’ll get hands-on experience and exposure to market trends.

Serious Collector: $50,000–$500,000 allows access to a mix of blue-chip Bordeaux, sought-after Burgundy, and premium emerging wines. You can diversify and hedge risks while still participating in auctions.

Ultra-Elite Portfolios: Millions of dollars, professional storage, private auctions, and occasionally a helicopter to fetch your new shipment from a chateau in Bordeaux.

Time horizon matters more than money. The best investment strategy is long-term: at least 5–10 years for appreciation, often 15–20 years for top-tier bottles. Wine requires patience, unlike crypto or meme stocks, which feed off instant dopamine hits.

Where to Buy Wine

Gone are the days when your only option was a local wine shop or European merchant. Today, the market is global and digital, giving investors unprecedented access.

Reputable Merchants: Longstanding merchants like Berry Bros & Rudd or Corney & Barrow remain reliable sources for vintage wine. They often provide advice, guaranteed provenance, and access to allocations for sought-after bottles.

Online Exchanges: Platforms like Liv-ex or WineBid allow you to buy and sell cases worldwide, providing transparency and pricing data. They are like the Nasdaq of wine.

Illustration 22: Buying wines online is becoming increasingly popular

Auction Houses: Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Zachys host live and online auctions for rare bottles. High stakes, high drama, the adrenaline is intoxicating.

Fractional Ownership & Apps: Platforms like Vinovest, Cult Wines, and Vint are revolutionizing the game. They allow: Fractional ownership of top wines, Automated storage in bonded warehouses, Market analysis and portfolio tracking, Access to auctions without leaving your couch and Simplified liquidity when you decide to sell. Using these apps, even a small investor can participate in the high-end wine market without needing to fly to Bordeaux or navigate private dealer networks.

Even digital or app-based investing requires strategy. A balanced portfolio might include: 50% Bordeaux: Stability, liquidity, and a history of growth, 30% Burgundy: Scarcity and upside potential, but more volatile, 20% Champagne & New World Wines: Diversification, emerging demand, and occasionally explosive growth.

Apps make balancing this mix easier. They can even suggest allocations based on risk tolerance, budget, and investment horizon. The point is clear: don’t put all your grapes in one basket. Even Romanée-Conti can fall in value if there’s a global glut or counterfeit scandal. Diversification protects your liquid wealth while letting the best bottles do the heavy lifting.

Ignoring Provenance: Apps usually verify authenticity, but always double-check. A fake bottle can tank your portfolio. Overpaying for Hype: Just because everyone is bidding on a Napa cult wine doesn’t mean it’s a good value. Relying Solely on Technology: Digital tools are excellent, but understanding vintage, terroir, and market psychology still matters. Chasing Quick Gains: Wine is long-term. Apps can show daily value changes, but flipping bottles too quickly can destroy returns and your sanity.

Illustration 23: Wine being produced in Georgia, a country famous for its wine produced at high altitudes.

Storage, Taxes and the perils of the wife life

Storage is important. You have to treat your wine as a newborn. Temperature has to be 12–14°C (55–57°F), no excuses. Humidity has to be 65–70%, not too dry or her corks shrink, not too wet or the labels rot. Avoid sunlight as UV destroys flavor and color. Avoid vibrations: no washing machines, no subways, no Tesla autopilot road trips.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/What-Its-Like-to-Tour-the-Worlds-Largest-Fine-Wine-Vault-FT-4-BLOG0124-3468d9b22d794b5382ff5e36c4b60860.jpg)

Illustration 24: Octavian Vault in UK, a former WWII munition storage that now is the world’s most secure wine vault.

Professional storage is worth every penny. Bonded warehouses like London City Bond or Octavian Vaults ensure optimal conditions and legal “in bond” status, meaning tax-free until sale.

Wine can be stolen, broken, or ruined by temperature spikes. Insurance policies protect your assets, often for 1–2% of total portfolio value annually. Pro tip: Include flood, fire, and theft coverage, and make sure the insurer understands the rarity and provenance of each bottle.

Many countries treat wine as a wasting asset, exempting it from capital gains tax. If stored in bond (warehouse), you often pay no VAT or sales tax until sale.

Local laws vary, always check before popping open that $25,000 bottle as a celebratory sale. Wine is one of the few tangible assets with tax efficiency baked into its storage methods.

Mistakes to avoid: Drinking your portfolio is Fatal, avoid bad storage even a perfect vintage becomes vinegar in poor conditions. Dont chase hype blindly, just because everyone wants a 2020 Napa cult wine doesn’t mean it’s worth the price. Ignoring provenance: No documentation = no liquidity.

Investing in Wine vs. Stocks

Wine is one of the few assets that has a track record of ouperforming the S&P500. See, wine investing isn’t about quick flips or timing the market. It’s about thinking like Warren Buffett — the ultimate “buy and hold” investor. Because the truth is, the best wines don’t just grow grapes; they grow value. And that takes time.

Illustration 25: Vineyards in Argentina

The magic starts to happen after around five years. Before that, the market is a bit of a wild ride shaped by shifting supply, unpredictable demand, and changing tastes. Even star wines need time before they start delivering those jaw-dropping returns.

Illustration 26: Saperavi grapes

Think of it this way: in the stock market, we analyze quarterly earnings, track revenue growth, and calculate intrinsic value per share. In the wine market? Each vintage is like an IPO of 100,000 “shares” bottles. Over time, people drink them. The supply shrinks, but demand often stays strong. Suddenly, your remaining bottles, your shares, become rarer, and therefore, more valuable.

That’s the essence of wine investing: you win by simply outwaiting everyone else. You’re not here for a quick 20% bump next month. This isn’t day trading — it’s more like owning real estate in a great neighborhood. The longer you hold, the better it gets.

And here’s the beauty of it: once you’ve made your picks, your job is basically done. No need to obsess over quarterly reports or panic over management changes. A great vintage doesn’t file earnings, it quietly matures, becoming more refined, more desirable, and more valuable with every passing year.

Imagine owning an asset you know improves with time an investment whose balance sheet, quite literally, ages like fine wine.

Owning your own Vineyard

For some investors, collecting and trading fine wine is only the beginning. The ultimate step — the one that turns passion into legacy — is owning the vineyard itself.

Buying a vineyard is not just an investment; it’s an immersion into an ancient craft and a tangible connection to the land. You’re no longer speculating on market movements, you’re cultivating value from the ground up. But while the dream of owning rolling hills of vines under the Tuscan or Bordeaux sun is undeniably romantic, the practical side demands careful thought, planning, and due diligence.

Capital and time commitment

A vineyard is a long-term, capital-intensive investment. The entry cost varies dramatically depending on the region, size, and quality of the land. In Europe, smaller estates in regions like Portugal or Southern France might start around €500,000–€1 million, while premium appellations such as Bordeaux, Burgundy, or Napa Valley can easily require several million euros or dollars. Beyond the purchase price, investors should budget for infrastructure, wineries, storage facilities, equipment, irrigation systems, and housing for workers which can add substantially to the total cost.

Illustration 27: Grapes in a Vineyard

Unlike traditional assets, vineyards take time to yield results. Newly planted vines generally require three to five years before producing marketable grapes, and full production potential may not be reached for seven to ten years. This makes vineyard ownership a play in patience and why many investors compare it to a blend of real estate and agriculture rather than a simple financial instrument.

Illustration 28: Harvesting at a French Vineyard

Location and Regulations

Geography is destiny in the wine world. The value of a vineyard is defined by its terroir, the unique combination of soil, climate, altitude, and micro-ecosystem that gives the grapes their character. Even two plots of land a few kilometers apart can yield wines of vastly different quality and price.

Investors must also navigate the legal and regulatory frameworks of their chosen region. In France and Italy, strict appellation systems (AOC/DOCG) govern which grapes can be planted, how the wine can be produced, and even how it’s labeled. In contrast, emerging wine regions such as Chile, Argentina, South Africa, and Australia offer more flexibility and lower acquisition costs, but may require greater marketing efforts to establish brand recognition and distribution channels.

Operation and management

Running a vineyard successfully requires both agricultural and business acumen. Most investors choose to hire an experienced vineyard manager and a skilled oenologist (winemaker) to oversee daily operations, crop management, and production quality.

Illustration 29: Roman mosaic. The operation of a vineyard has not changed much since Roman times.

Labor costs, seasonal fluctuations, and unpredictable weather events, such as frost, drought, or disease, can all significantly impact annual yields and profitability.

ome investors take a hands-off approach, leasing the land to an established producer or entering a joint venture with a winemaking company. This model reduces risk and operational involvement while still allowing for long-term capital appreciation of the land and brand. Others prefer a boutique or lifestyle model, producing smaller quantities under their own label for niche luxury markets, hotels, and private clients.

Illustration 30: Grapes being harvested at the Madeira Wine festival.

Market, Distribution and Brand Building

Owning a vineyard is only part of the equation, selling the wine profitably is the other half. Building a recognized brand takes time, marketing expertise, and consistent quality. Investors must understand distribution networks, export regulations, and pricing strategies. In established markets, competition is fierce, but a strong story, authenticity, heritage, or sustainable practices can make all the difference.

Modern trends favor vineyards that focus on organic or biodynamic farming, low-intervention winemaking, and carbon-neutral operations. These not only appeal to a growing segment of eco-conscious consumers but can also command premium pricing and attract institutional investors seeking ESG-aligned opportunities.

Risk and Reward

As with any long-term investment, vineyards carry both financial and environmental risks. Climate change poses one of the greatest challenges to viticulture, with rising temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and water scarcity affecting yields and quality. However, this also opens opportunities for innovation, from investing in drought-resistant grape varieties to adopting precision agriculture and AI-driven vineyard management.

The rewards, however, can be substantial. A well-managed estate can generate income through wine sales, vineyard tourism, and land appreciation. Some investors diversify by developing luxury accommodation or wine experiences on the property, turning their vineyard into a profitable destination.

And beyond the balance sheet, there’s the intangible return . owning something timeless, rooted in nature, culture, and craft. A vineyard is not just an investment in land; it’s an investment in legacy.

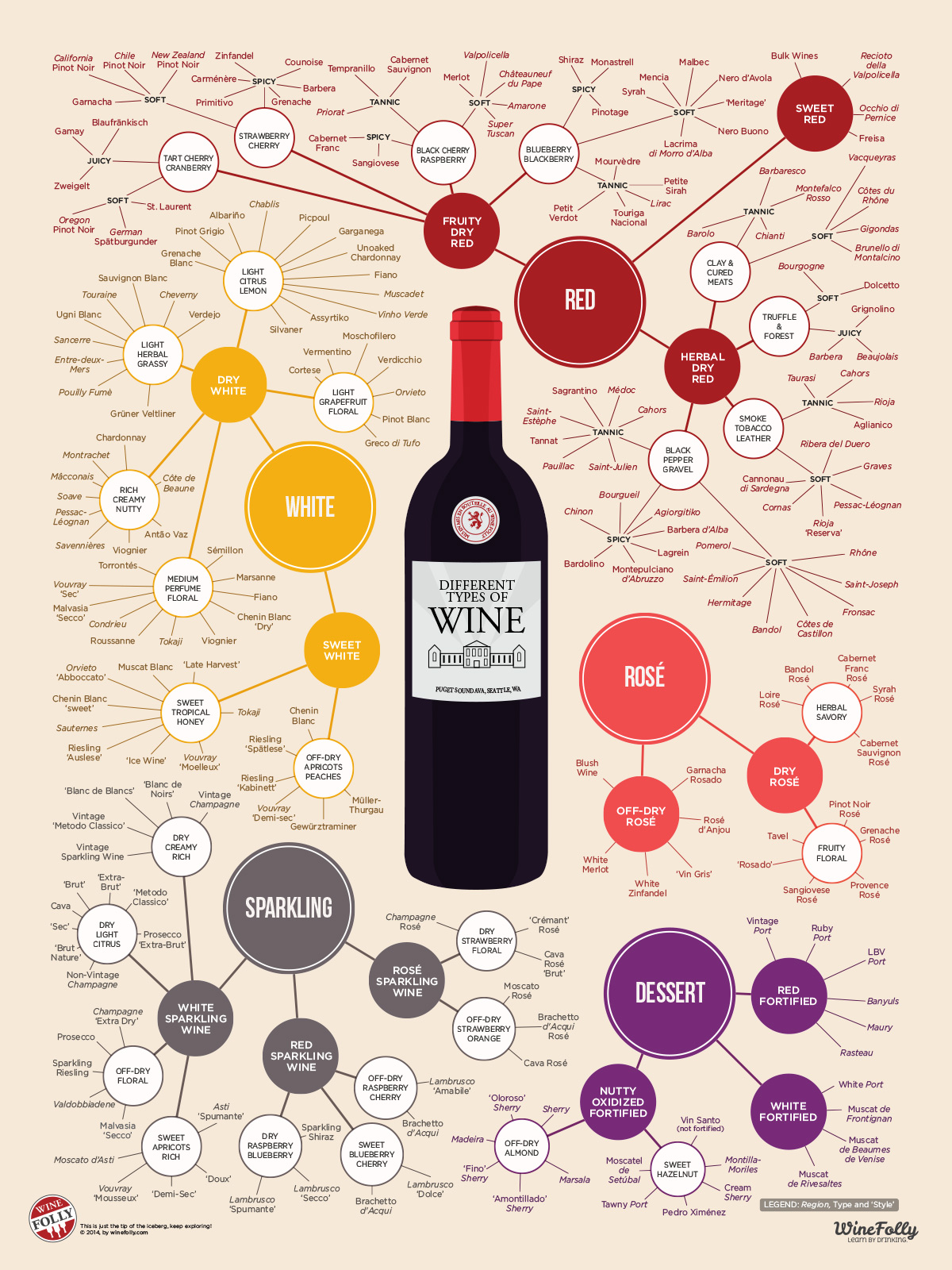

Illustration 32: Full overview of all types of wine, gathered from Winefolly